Last year, Jacob Kushner, a journalist living in Kenya, reported on his observations from villages in which GiveDirectly had distributed some of its earliest cash transfers. This year, we funded him to report on the National School-Based Deworming Programme in Kenya, a program supported by Deworm the World.

Mr. Kushner’s article follows. His colleague, Anthony Langat, observed the program and interviewed some stakeholders; his interview notes are posted here.

In addition to Mr. Kushner’s article:

- We summarize our takeaways here.

- Evidence Action, which runs Deworm the World, responds to the article here.

School-based deworming: A parent’s perspective

In Kenya, some parents fear potential, minor side effects of deworming, and a few may even oppose it for religious reasons. Others say they just want to be better informed.

By Jacob Kushner and Anthony Langat

Since 2009, Evidence Action’s Deworm the World Initiative has provided technical assistance to the highly praised government-run National School-Based Deworming Programme, in Kenya. Last year the program de-wormed 6.4 million students in 16,000 schools. The Deworm the World Initiative encourages a multi-faceted strategy toward informing parents about the program, using radio announcements, community meetings, and by training teachers to encourage students to let their parents know about the program in advance of each ‘deworming day.’

But to ensure that each and every parent is made aware of it beforehand is impossible. Many families in rural Kenya lack radios, and communication between schools and certain families can be limited. And it’s safe to assume that children don’t always dutifully relay to parents each and every announcement they hear in class.

In March, Anthony Langat traveled to Kenya’s western Siaya county to observe deworming day at several schools. In Siaya county, over 312,000 students were targeted for deworming on that day. Over the course of a week he interviewed 13 parents, four teachers and one government official as well as three of Evidence Action’s staff members. He was surprised to find that many of these 13 parents said they were poorly informed or entirely uninformed about the March deworming before it occurred and that some were upset about that fact.

Parents want more information

Julius, a 65-year-old farmer and father of six, said he was disappointed that he wasn’t informed as to what, precisely, the deworming treatment consisted of, nor of its possible side effects.

Julius said that he eventually came to learn more about the drug’s purpose, and that in the future he’d encourage his children to participate. “I will accept when they come next time. But I need a written form stating what they are going to give my child. Just a form that has information regarding the drug so that we know and stay informed,” he said.

Evidence Action staff said the deworming program is part of Kenya’s overall government school health program for children, which does not require parental permission for its individual school based treatments. Even so, Evidence Action supports training of local government agents such as Community Health Extension Workers (part of Kenya’s Health Department) to reach out to parents and communities to inform them about the deworming. The program’s community sensitization efforts include meetings with regional stakeholders, public county-level launch events, displaying posters, and public service announcements via radio. (Originally, staff tried paying a vehicle to drive around with someone announcing the program over loudspeakers, but that seemed to have less reach than radio. Some parents who were interviewed acknowledged how difficult it would have been to inform them in advance, noting that they themselves did not have working radios).

“It’s important for everybody in the community to have an awareness of what’s going on so that people feel comfortable sending their children to school to receive deworming medication and to increase the awareness of why deworming is a positive thing for communities,” said Grace Hollister, Director of the Deworm the World Initiative.

One of the most effective ways to inform parents seems to be through teacher training.

“You will find that a teacher is very well trusted in the society. Whatever the teacher says or tells the children, it is usually taken as a gospel truth. So when they tell people that their children will be dewormed, they (parents) are very sure of what the teacher has told them,” said Charles Ang’iela, District Education Officer for the sub-county of Rarieda in Western Kenya. “The teachers are playing a very crucial role.”

One parent, a 57-year old mother, seemed to echo that sentiment, suggesting teachers invite parents to discuss the program in advance. “If parents could have been called to a meeting in school and told of the deworming rather than sending the children, the information could have been received better by parents,” she said.

Children, parents, fear sickness brought on by pill

Beyond the concern over lack of prior information about the process, a few parents said their children had become sick from taking the de-worming pills, and teachers shared some anecdotes of students vomiting or becoming dizzy after taking the pill.

Julius, the father who expressed concern at his lack of information about the treatment, said the reason he was hesitant this time is that his daughter became sick from a previous deworming. “We thought it was malaria and we took her to the hospital,” where he was informed that her stomach had likely simply reacted poorly to the de-worming pills, he said. Julius said that this time around, his daughter didn’t attend school the day of the deworming. His 11-year-old son did, and Julius said he too experienced side effects of the pill.

“After he was given the pills at school, I was called (and told) that the boy had fallen sick on the way (home) and could not walk,” Julius said. “When I found him he was dizzy, and looked tired and unable to walk. I took him on my bicycle and brought him home. Upon arriving he started vomiting.”

Julius said that “When I was called that he had fallen sick because he had taken the drugs I was angry.” (The boy’s teacher, who escorted reporter Anthony Langat to the boy’s home later in the day, confirmed that on the day of the deworming the boy was sick to the point that he was unable to walk home by himself).

Jael, a 29-year-old mother of four who owns a few acres of land where she grazes cattle and raises chickens, said two of her children have also become sick from the deworming treatment. This deworming day, one of her sons refused to take the deworming pills at school. The boy’s teacher said he told her that his parents told him not to participate.

“I didn’t tell them not to take the pills. My son just feared the drug,” said Jael. “The other time my daughter felt dizzy and vomited so she feared and even the other siblings feared.”

A teacher at Ramba Primary school said that when he informed his students the day before that the deworming program was to take place, some of them reacted negatively due the side effects they’d experienced during previous dewormings. “‘What, PZQ?’” he recalled some of them saying. (PZQ refers to drug praziquantel which is administered in some parts of Kenya to treat schistosomiasis, a disease caused by a waterborne parasite. Albendazole treats the soilborne parasite helminths, which is more common in Kenya and therefore albendazole is administered to a larger target population than PZQ. Both drugs are approved by the World Health Organization.) “‘Over my dead body, I will not take that drug again. The way it reacted with me? No, no, no, I will not take it.’” A teacher at Gagra Primary School recalled a 2013 deworming in which about six of his students fainted, having taken PZQ.

Hollister said “there is the potential that there could be some side effects because of the medication, which can happen especially to children with very large worm loads, for example stomach pains.”

Kenya’s government recommends a detailed protocol for mitigating and responding to side effects brought on by the pill. Teachers undergo a half day of training during which they’re instructed to keep students in class for two hours after a de-worming so as to observe whether any suffer side effects. They’re given phone numbers for doctors who are on-call nearby and they’re advised to locate and find contact information for the closest hospitals in advance of a deworming.

A small minority of parents may fear deworming for religious reasons

Teachers and Evidence Action staff said on rare occasions some parents may quietly but intentionally not send their children to school on de-worming days because they object to it for religious reasons. No parents interviewed for this article expressed this sentiment, but staff presumed that those parents who do withhold their children from deworming for religious reasons may mistakenly associate the pill with infertility, contraceptives or abortion.

The head teacher at Ramba Primary school said about 10 of the school’s 900 or so students refused to take the pill. “Some were because of the parents and the denomination factor—some kind of cult within their church could not allow them to take the drug,” he said, referring to one local church called Roho Israel. “Some parents also tried to demonize praziquantel (PZQ) unfairly just because of the dizziness and all that. So there is that kind of fear and fright that some people would say that you may collapse and fall down.”

A teacher at Gagra Primary School said five of his female students were afraid that the drug could cause infertility. “I do not know how the parents were connecting it to that,” he said. (A teacher at another local primary school, Lwak, said he hadn’t heard of any cases of parents refusing to let their children participate for religious reasons.)

“You know, this school is sponsored by (the) Catholic Church, and the population around here is mostly Catholic,” said Dickson Akawo, another teacher at Gagra Primary school. He said that for some parents, “what is in their mind is that even this (drug) has some sort of sterilizing effect on them. So the parents can deter a child from coming during the deworming day.”

“What they do not know is that we can become so clever,” said Akawo, describing how he and other teachers stock extra pills on deworming day in order to deworm students on subsequent days because “we know the repercussions of somebody not being dewormed.”

Kenya director for Evidence Action’s Deworm the World Initiative Thomas Kisimbi said that while the program does allow for extra drugs to be administered to students who may have missed it, he said the program doesn’t sanction teachers’ administering the pill to children who they believe missed it the first time due to objections by them or their parents.

Kisimbi estimated that only a few hundred children out of the more than 6 million who are dewormed through the program refuse to take the pills for religious or cultural reasons. (Hollister suggested that even those few may be geographically confined to just certain sub-counties). Toward convincing such parents to agree to the deworming, Kisimbi said “The best we can do is provide information and for them to make an informed decision around that.” Beyond that, Kisimbi said some of those parents are bound to eventually notice that other children undergo health improvements as a result of the program and therefore come around.

Parent’s priorities

Many parents interviewed said that they were far more concerned with malaria than they were with parasites. Kisimbi said this is likely due to the fact that Malaria has the potential to kill, whereas worms only sicken their children. Some parents cited other health concerns such as lack of clean water, and one father said that while schools implement the deworming program, they often fail to address other, important health issues. “I even urge teachers in school to ensure that children wash their hands before they eat,” the parent said.

Ang’iela, the government official, agreed that parasites are one of many health issues that plague children here, but cautioned that parents aren’t always aware of how seriously parasites do affect their children.

“You know, the traditional approach to life here is still strong whereby some people think that water is water so long as it is lake water, fruit is a fruit so long as it is a fruit that nobody has touched,” Ang’iela said. “They only see that their hands are dirty when they see charcoal on it and even that charcoal they will just rub it off and continue eating. So there is a lot of work which still needs to be done from this traditional approach, but that in my opinion has continued exposing them to things like worms.”

For his part, Kisimbi said the most urgent challenge for Kenya’s deworming program isn’t addressing fear of side effects or parent’s concerns about the drug. Rather, it’s how to get students who are not enrolled in school—or whose schools are not legally registered with the government—in for treatment. And in the long run, for the program to continue, Kenya’s government will have to buy in further.

“We want this program to go on 10 years, 20 years beyond the [involvement] of Evidence Action and we want the government to be able to take greater responsibility over the program,” he said.

In most respects, the National School-Based Deworming Program seems to be working quite smoothly. There were no indications that children who attended school on the March deworming day were being missed, that pills were not arriving at the correct locations, or that teachers were insufficiently trained in administering them. For their part, teachers unanimously noted significant improvements in class attendance, presumably a result of the reduction in parasites affecting their students. And nearly all the parents interviewed—even those who wished they had been better informed about the program—said they viewed the program favorably and were glad their children were being dewormed in school. Many parents said their children were sick less often and missed fewer school days as a result of an improvement in their children’s health they attributed to the dewormings.

This reporting offers merely an anecdotal look into the question of whether parents are sufficiently informed about the program. Elsewhere, Evidence Action is already working to determine the extent of parent satisfaction and knowledge and how to improve both. In India they are conducting a human centered design process, interviewing parents, teachers and other actors in the deworming process to determine what precisely each want to know about the process and how to best deliver that information in a cost effective way. Similarly, in Uganda Evidence Action was working with a human-centered design firm to understand consumer behavior toward using chlorine in drinking water so as to better inform families with small children.

Jacob Kushner is an investigative journalist currently based in East/Central Africa and the Caribbean. He reports on development economics and inequality, foreign aid and investment, governance and innovation in developing nations. Anthony Langat is a Kenyan journalist living in Nairobi.

GiveWell’s response

We are excited that we were able to commission Mr. Kushner and Mr. Langat to visit the Deworm the World Initiative on the ground in Kenya. (We previously commissioned Mr. Kushner to report on GiveDirectly’s operations in Kenya.)

To date, the information we have on the Deworm the World Initiative has come from (a) Deworm the World Initiative staff, (b) monitoring and evaluation information provided to us by the Deworm the World Initiative, and (c) our own site visit to the Deworm the World Initiative in India. Mr. Kushner and Mr. Langat’s visit represents a different perspective on this program, and a chance to identify issues we couldn’t have otherwise.

The intensity of our research process gives us confidence that we’ve likely identified and considered key issues relevant to our top charities, but we’re also aware that we may have missed some. Our goal in asking Mr. Kushner and Mr. Langat to visit top charities in the field is to reduce the likelihood that we have missed any major problems. Mr. Kushner and Mr. Langat did not encounter any problems of this sort. Overall, their report is consistent with our expectations, and it bolsters our confidence in the Deworm the World Initiative.

Based on information from randomized controlled trials, we know that the pills used in combination deworming programs can sometimes cause relatively benign side effects (more in our intervention report). We are also not surprised that some parents say that they are less informed than they would like to be about the program.

We believe these issues are worth addressing, but we don’t think these costs come close to outweighing the benefits that the program provides.

Finally, we would not expect it to be hard to find similar examples were someone to interview recipients of other aid programs. It is worth keeping in mind that very few aid agencies have allowed themselves to be subject to this type of analysis, so we are grateful to support an organization like Evidence Action (which runs the Deworm the World Initiative) that is ready to open itself up to outside criticism.

Evidence Action’s response

To GiveWell and Jacob Kushner:

We appreciate the time that Jacob Kushner and Anthony Langat spent with Kenya’s National School-Based Deworming Programme, and with Evidence Action’s Deworm the World Initiative. Evidence Action provides technical assistance to this evidence-based program of the Kenyan government.

The writers’ time is paid for by GiveWell which we hope is clearly disclosed. Anthony Langat, one of the writers, visited Siaya county during the most recent school-based deworming day (Jacob Kushner did not visit the communities). During that day, 312,226 children were targeted for deworming in their schools; more recently, in early June 2015, more than 2 million children received treatment for parasitic worms in counties across Kenya. In the last school year (2013/14), 6.4 million children were dewormed as part of Kenya’s national program, and this year the program is on track to deworm a similar number of children.

We appreciate that the journalists are trying to find out what parents understand about the National School-Based Deworming Programme. We are naturally keenly interested in this aspect of the program as well, as teachers and parents are very important in making school-based deworming a success.

However, there are a few important points to remember:

- Kenya’s National School-Based Deworming Programme is a government program, jointly implemented by the Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Education, Science, and Technology. The Kenyan government administers a variety of public health interventions through its public schools and has the full and final say on all such programs and how they are run. Such school health programs are promulgated by the government to ensure children have equitable access to quality health services; the National School-Based Deworming Programme is one such program. We provide technical support to the government on implementation of a cost-effective, high coverage program; assist in developing procedures and protocols; and serve as the coordinating body for the program.

- We do not think that this article evaluates parental knowledge and involvement in a rigorous or scientific manner. Anthony Langat chatted with 13 parents – a highly anecdotal and non-representative sample. A few parents that he spoke to expressed confusion about the reason for why children received deworming treatment. We very much regret that these parents had a less than desirable experience. Incidentally, the side effects of receiving treatment for parasitic worms that one parent noted — nausea and vomiting — are actually associated with very high worm loads in children, making the child’s parasitic worm treatment all the more important.

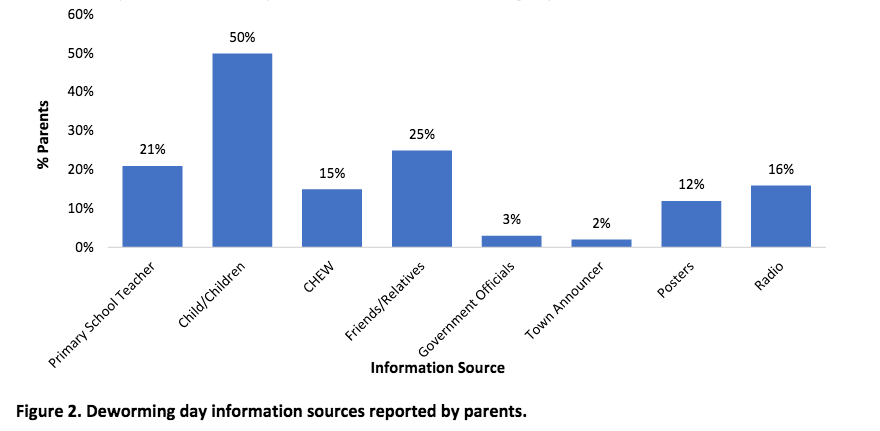

In a representative survey of parents that we conducted at the beginning of the 2014/15 school year to assess parental awareness about deworming, we found that 21% of parents were informed about Deworming Day by their child’s teacher and 50% of parents by their child. Poster, radio, and community health extension workers (“CHEW” bar in the figure below) were other significant sources of information about Deworming Day (n=308 parents in 53 schools, Q3 2014, multiple answers were possible so total is >100%).We continuously evaluate the quality of the outreach of the program with representative surveys (rather than anecdotal stories) and suggest to the ministries ways to improve community awareness.

As the authors noted, we are also engaged in a detailed qualitative study in India to better understand how to improve the government’s training cascade that conveys information about deworming all the way to every teacher, classroom, and families. We are nearing the end of this assessment that will yield important lessons for deworming programs in other countries as well.

- Most importantly, we want to emphasize this point that got lost in the piece by Kushner and Langat: All who are involved in the National School-Based Deworming Programme are keenly concerned about the health and safety of children. The children and their well-being are all of our utmost priority. That is why we engage in school-based deworming in the first place. As a result, children’s safety always comes first.

There are two points to be made on this matter: First, the drug given for the majority of deworming treatment in Kenya, albendazole, has a remarkable safety record. Hundreds of millions of patients have taken the drug all over the world over the last 20 years. There is extensive data on the minimal adverse experiences. Side effects reported in the published literature are extremely low. Gastrointestinal side effects, the main side effect, occur with an overall frequency of less than 1%. A second drug, praziquantel, is administered in communities endemic for schistosomiasis – this is a subset of the overall communities treated by the program. It is recommended that children are provided with food prior to the administration of praziquantel, to minimize nausea and other minor side effects of the medication. Like albendazole, this drug is considered very safe for treating school-age children.Second, the Kenyan government, with our assistance, has implemented a strict and rigorous ‘adverse event’ protocol. This is standard procedure for all national deworming programs and every last person involved in deworming is extensively trained on procedures. The protocol is here.

The Adverse Event Protocol contains these elements:

- Prescribes the protocol for preventing adverse events such as emphasizing the importance of not deworming sick children;

- Emphasizes importance of relevant training messages (i.e., making sure drinking water is available, that children chew albendazole tablets, and if treating for schistosomiasis, that children eat beforehand);

- Clarifies the difference between mild adverse events and serious adverse events and gives examples of each;

- Prescribes the actions to be taken for managing adverse events on and after deworming day;

- Explains the need to ensure children have eaten prior to praziquantel administration – the program also provides funds for school feeding on treatment days to schools in high-need areas;

- Establishes an emergency response team and phone trees to ensure school personnel connect with appropriate health providers and the affected child’s parents;

- Lists contact information for local medical officers and emergency response team;

- Includes reporting forms and protocol for mild and serious events.

Kids’ safety and health will always come first and that is why the government of Kenya has implemented this national program.

- The detrimental health effects of parasitic worms are profound. 6.4 million kids have better lives because of being dewormed once a year. Now entering Kenya’s fourth year of the national program, the government of Kenya is closing in to eliminate parasitic worms in Kenya as a public health threat. Worm prevalence rates in Kenya rapidly dropped by more than 20% in the last two years to the point where the country is nearing just a few percentage points prevalence in several counties. The government of Kenya is very forward looking with this health policy and at the vanguard of protecting the lives of its children. Similarly to how the U.S. American South eliminated worms as a public health threat at the turn of the century, Kenya, as a fast-developing country, is protecting its children from the devastating health effects of parasitic worms. We applaud the government of Kenya in implementing what is a best buy in development and good public health policy.

We would urge GiveWell and the journalists to continue to be rigorous in evaluating the programs it recommends.

As more governments in countries with high worm burdens roll out national school-based deworming programs, we are ever so much closer to eliminating the public health threat of parasitic worms in children worldwide. Significant progress is being made — and hundreds of millions of children have a brighter future as a result.