The Chronicle of Philanthropy and NPR note that charities don’t seem to have spent large percentages of the funds raised for Haiti to date. Here we (a) lay out the numbers, using the Chronicle of Philanthropy’s helpful public survey data; (b) discuss what it means for donors that most of the money raised seems to be reserved for long-term as opposed to immediate relief.

The numbers

The Chronicle of Philanthropy’s survey data gives a total of over $1.6 billion raised, and seems to include nearly all of the “big name” charities working in disaster relief. We have collected the data, for all charities that provided comparable “raised” and “spent” figures (i.e., either both worldwide or both non-worldwide), into this Excel file.

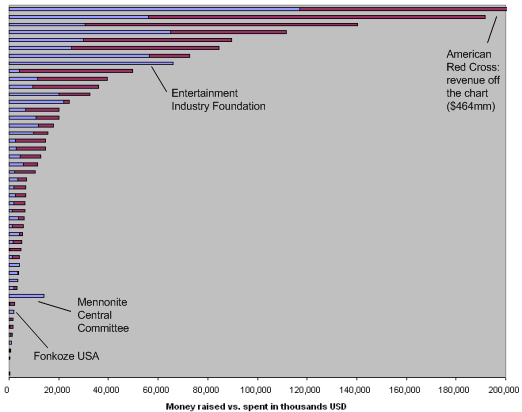

The chart below summarizes this data by sorting the charities in order of how much they’ve raised. Each bar represents a listed charity; the total length of the bar corresponds to funds raised, while the blue part corresponds to funds spent.

Notes:

- 38 of the 48 charities have spent under 75% of the money they’ve raised; 29 of the 48 have spent less than half the money they’ve raised; and 22 of the 48 have spent less than a third.

- The Mennonite Central Committee reports spending far more than it has raised, but its numbers are confusing (it is the only listed charity whose “worldwide” money raised figure is lower than the other figure it provides) and there is no summary of how it’s spent the funds.

- The Entertainment Industry Foundation reports raising and spending exactly the same amount ($66 million). There is no summary of how it’s spent the funds.

- Only two other charities, Population Services International and Fonkoze, report spending over 90% of what they’ve raised. Both cases involve relatively small amounts (around $2 million for Fonkoze and $211,000 for Population Services International). Update: this Fonkoze figure is for Fonkoze USA, not for Fonkoze as a whole.

Overall, about 38% of the ~$1.6 billion raised has been spent. In fact, the amount spent – around $627 million – is not much greater than the amount ($560 million) that was raised in the first 9 days after the earthquake hit.

Why this matters: “speed relief” vs. longer-term relief and recovery

We don’t believe that spending money slowly indicates irresponsibility. Shortly after the earthquake hit, we expressed doubts about whether there was “room for more funding”, and the Chronicle’s coverage implies that at this point there largely isn’t.

However, we do feel that it’s important for donors to note how much of their donations are likely paying for longer-term, as opposed to immediate, relief, because this has implications for what one should look for in a disaster relief charity in the future.

Immediately after the earthquake hit, many (including us) were stressing the importance of a charity’s existing capacity on the ground and its ability to respond quickly and efficiently. When we think about longer-term relief, though, we wish to focus less on capacity/speed and more on the things we usually focus on:

- Is the organization clear about where the money is going?

- Does the organization formally assess whether and to what extent its work is succeeding? (For disaster relief, in particular, we’d hope to see evidence that the organization is actively getting and acting on feedback from beneficiaries.)

- Does the organization focus on activities that help as many people as possible, as much as possible, for as little money as possible?

In assessing disaster relief organizations, we plan on focusing on what they’ve accomplished over the longer term, because that’s what donations in these situations are most likely to be paying for.