Just because someone is repaying their loans doesn’t mean they’re benefiting from the loans.

We have given some conceptual/anecdotal support for this idea in the past, linking to David Roodman’s posts on possible “overlending” and comparing microloans to payday loans. Lately we’ve been investigating something a bit more concrete: how often, and why, do microfinance clients “drop out” of microlending programs?

The basic idea is that a client could repay a loan due to pressure (from their “lending group” or the microfinance institution), making sacrifices or borrowing from elsewhere (such as moneylenders) to do so. We would expect such clients to show up as “repayers” while not necessarily staying in the program for more loans.

Our observations (details and full sources below):

- Dropout rates appear substantial, averaging 28% and often exceeding 40%, among institutions that publicly report them (via MixMarket).

- Survey data on why clients drop out is limited, but what we’ve seen suggests that “graduation” (i.e., moving to better sources of credit or no longer needing credit) is not a common reason for dropping out. Business failure and dissatisfaction with the group/staff/institution are common reasons.

- A high dropout rate can be consistent with reasonably good reported client satisfaction.

Dropout rates

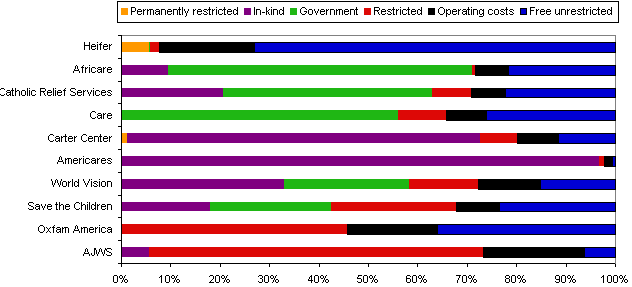

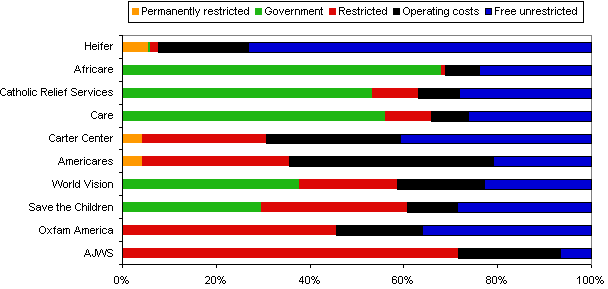

We have gone through all microfinance institutions that report “social performance reports” on MixMarket (you can see the complete list of institutions, with their publicly posted reports, at MixMarket’s social performance report section) and collected the data into this spreadsheet (XLS). (Note that dropout rates are not on the list of “standard” indicators and are not reported by all MixMarket participants, but are included in “social performance reports.”) Here’s a summary of the 60 institutions that report dropout rates:

| Dropout rate range | # institutions |

|---|---|

| Exactly 0% | 3 |

| 0% to 5% | 7 |

| 5% to 10% | 4 |

| 10% to 20% | 10 |

| 20% to 40% | 23 |

| 40% to 60% | 12 |

| 60% to 80% | 1 |

| 80% to 100% | 0 |

Taking the average across all 60, weighted by number of clients, yields an “average” dropout rate of 28%. Details here (XLS). That implies that in a given year, 28 out of 100 clients become non-clients (see the “social performance reports” for the details of the calculation).

Reasons for dropping out

We don’t know of any comprehensive studies of the reasons clients drop out, but in the process of searching for an outstanding microfinance institution, we have encountered several small-scale surveys. We have posted the non-confidential dropout surveys along with a summary in Excel, and hope to clear a couple more in the future (they are broadly consistent with the summary below).

The Bangladesh study specifically states that “One of the reasons that is notable by its almost complete absence from these listings of grounds for drop-out is ‘graduation’” (pg 4). The rest of the studies give the same picture: “graduation” (i.e., the idea that clients now no longer need microfinance because they can access better sources of credit and/or do not need credit) is not cited as a significant factor in any of them, except in the Uganda study (which does not state how common this factor is, but cites it as a factor specifically for “Relatively Well-off drop-outs” (pg iii)).

Business failure is a commonly cited factor (37-58% of clients cite this factor, in the studies that report numbers – see Excel summary). Issues with the “lending group,” the organization or its staff are the other most common factors. The Tanzania study cites “The inability of clients to cope with the rigid MFI policies and procedures” (pg 9) and also vividly describes a group conflict in which the treasurer claimed funds had been stolen (pg 10). The Bangladesh study states that “One of the key determinants of drop-out … is the insistence by field staff that clients take loans” (pg 3-4).

Client satisfaction

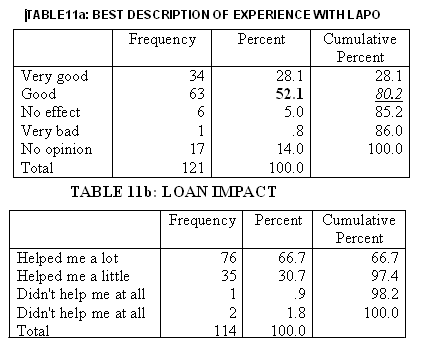

The LAPO study (see previous discussion of LAPO, Kiva’s largest partner) looks not only at the reasons for dropping out, but at overall reported client satisfaction.

The former figures seem cause for concern: there is a dropout rate of around 25% (estimated from graph on pg 7) and reasons given include “poor business performance” (applying to 24.2% of dropouts), “Burden of paying for others who had defaulted” (29.5%), and “the attitude of some staff” (cited as a major factor but without quantification). But overall, reported satisfaction looks reasonably strong:

(Note that the repeating of “Didn’t help me at all” is found in the original table.)

We feel these numbers should be taken with a grain of salt, since it seems possible to us that clients could have felt pressure to report positive experiences. But the numbers do serve as a reminder that microfinance institutions have many clients who are (apparently) happy repeat customers.

Bottom line

Most microfinance institutions don’t appear to publicly report dropout rates, much less the reasons for dropping out (this observation based on the small percentage of MixMarket participants who have shared social performance reports). Those that do are likely to have more encouraging numbers than the others, and yet their numbers seem to leave substantial room for concern. Clients seem to drop out, for overwhelmingly negative reasons, at rates averaging 28% and often exceeding 40%.

We don’t mean to overfocus on the negative here. Microfinance institutions could be providing valuable services for many people, and we wouldn’t want donors to stay away from an activity that’s doing good overall even if it is doing damage to some.

But it does seem that the more we dig through the information on microfinance, the less it resembles the stories commonly told about it. Making loans can do good or harm. We feel strongly that people donating money to microfinance institutions should be asking for substantial due diligence – not anecdotes and pictures, and not the commonly cited, misleading metrics like “repayment rate,” but systematically collected information that gets at services’ actual impact on clients.