Recently, we’ve criticized (in one way or another) many well-known, presumably well-intentioned charities (Smile Train, Acumen Fund, UNICEF, Kiva), which might lead some to ask: should GiveWell focus on the bad (which may discourage donors from giving) as opposed to the good (which would encourage them to give more)? Why so much negativity and not more optimism?

The fact is, we are very optimistic about what a donor can accomplish with their charity. Donors can have huge impact — save a life, improve equality of opportunity, or improve education. Our research process, and our main website, are (and always have been) built around identifying outstanding charities.

GiveWell hasn’t set a bar that no charity can meet. Six international charities have met and passed the bar. Where most charities fall short, they succeed.

The problem is: because the nonprofit sector is saturated with unsubstantiated claims of impact and cost-effectiveness, it’s easy to ignore me when I tell you (for example), “Give $1,000 to the Stop Tuberculosis Partnership, and you’ll likely save someone’s life (perhaps 2 or 3 lives).” It’s easy to respond, “You’re just a cheerleader” or “Why give there when Charity X makes an [illusory] promise of even better impact?”

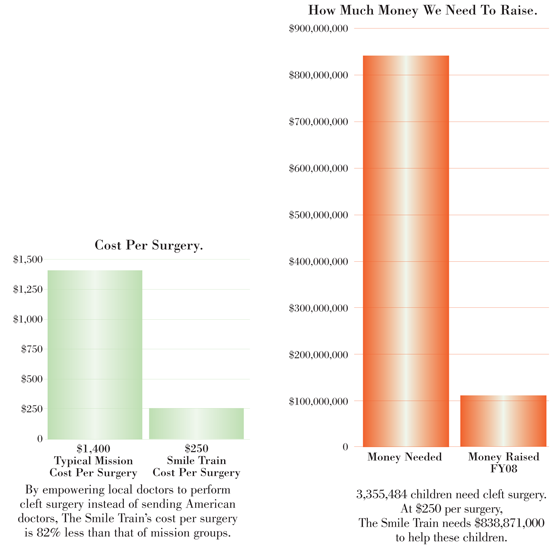

We don’t report on Smile Train, Kiva, Acumen Fund, UNICEF, or any others for the sake of the criticism; we write about them to show you how much more you can accomplish with your gift if you’re willing to reconsider where you’re giving this year.

Unless you have strong reason to believe otherwise, I’d recommend you choose a great charity as opposed to one that’s merely better-than average. If you only have a fixed amount to give, why not support the very best?