The goal of Cause 1 is to save lives in Africa, and we estimate that a good strategy can save a human life for somewhere in the ballpark of $1000. Sounds like an unbelievable deal, right?

Not to everyone. I was recently talking to a Board member and mentioned how much cheaper it seems to be to change/save lives in Africa vs. NYC. He responded, “Yeah, but what kind of life are you saving in Africa? Is that person just going to die of something else the next year?”

I think it’s interesting how (a) completely fair, relevant and important this question is for a donor; (b) how rarely we see questions like this (“Sure I helped someone, but what kind of life did I enable?”) brought up and analyzed. Here’s what we know right now:

(Data for what follows comes from the Disease Control Priorities Project. More detail is available on the the life expectancy page of our main site.)

Approximately 80% of children born in sub-Saharan Africa reach age 5; in the developed world, it’s 99%. The main contributors to the difference are:

- Malaria

- Respiratory infections (pneumonia and bronchitis)

- Diarrheal diseases

- Perinatal conditions (deaths in childbirth)

- Measles

- HIV/AIDS

Measles is the easiest to prevent (just use a vaccine); diarrhea can be prevented with better sanitation and treated with a cheap packet of nutrients; malaria risk can be substantially reduced through use of bednets; the other three generally take some sort of skilled medical care, although improved nutrition may reduce just about everything.

Between ages 5 and 45, people in sub-Saharan Africa have relatively similar mortaility rates to those in the developed world except for the influence of HIV/AIDS, TB, and mothers dying in childbirth. Around age 45, a lot of the same diseases that kill people under 5 start killing again (maybe due to weakened immune systems).

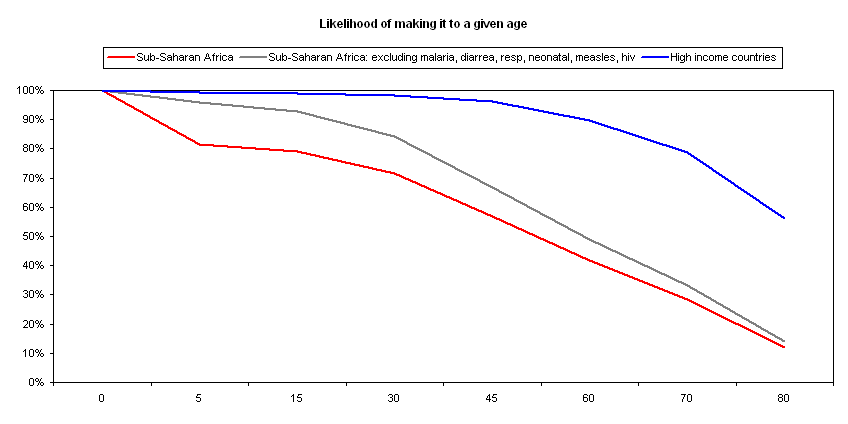

The following chart shows the probability of making it to a given age (assuming you reach age 5) of (a) a child born in sub-Saharan Africa, (b) a child born in sub-Saharan Africa who survives HIV/AIDS, TB, and maternal conditions during adulthood, and (c) a child born in the developed world.

And the following is the same idea, but from age 5 on – i.e., if you can use a comprehensive child care program to reduce infant mortality, this is what you can expect to get.

So what’s a life saved? If you save someone right as they exit infancy (5 years old), you’ve saved someone who probably has around a 50% chance of making it to age 60 … another way of putting this is that if you save two lives (very very rough estimate of cost: $2000), you’ve in expectation given one person a full life that they wouldn’t have had. (You’re actually getting more than this, of course, since a person has a 75% chance of making it to age 30, but let’s keep it simple.)

And yeah, maybe the life you saved is a life without iPhones, but we’re still talking about a person who, at the very least, can be expected to grow up, make friends, fall in love, get in arguments, watch the sunset, have ups and downs, etc. Not bad for $2000.

As always, lots of questions remain, including:

- Is someone at risk from one disease also more likely to die of another (weaker immune system in general)? For example, when you save a 5-year-old who would have died of malaria, does that 5-year-old really have a 50% chance of making it to age 60, or less because only those with weaker immune systems are at risk in the first place?

- What is the general health we can expect for a saved life in sub-Saharan Africa? A few of the preliminary statistics we’ve seen on malnutrition and “neglected tropical diseases” (largely parasite infections) are pretty sobering, but we don’t know enough to say for sure how likely someone who lives till age 60 is to be highly debilitated vs. poor but basically healthy.

But, right now we still think there are pretty awesome deals to be had from a good charity in Africa (no such promises made for a charity that can’t demonstrate its cost-effectiveness), and we continue to explore the issue.

Comments

Honestly I tend to pride myself on my general realism regarding the risks and dangers of life, and among illusions relating to those risks, appreciating how rare violence is and how little it effects life expectancy ranks high, yet even so I’m surprised to see that even in Africa violence contributes so little to over-all death rates. 800K killed in Rwanda, 50K murders/year in South Africa, 4M in the Congoese civil war, Sierra Leon and Liberia, all of this is just a drop in the bucket compared to poverty, but of course it is. 900M people live in Africa, and if a few percent of them loose half their life expectancy to violence total life expectancy is reduced by half of a few percent.

A truly surreal thought is that eliminating all of the violence in Africa would raise African life expectancies by less than the difference in life expectancy between the US and France or Sweden!

Heya Holden,

Just checked out your blog from the comments on Gift Hub. I left a little note there for you.

Appreciate your work. So glad that there are people asking hard questions, happy to be comfortable with uncomfortable answers when they come.

It was refreshing to find among the statistics your comment:”we’re still talking about a person who, at the very least, can be expected to grow up, make friends, fall in love, get in arguments, watch the sunset, have ups and downs, etc.”

I’m very glad for the stats too.

I think I might just subscribe – seems like something feisty and interesting is happening here.

If the life expectancy of a black child in the inner city is say, 10% less than that of a white baby in a wealthy suburb, is saving the black child’s life worth 10% less than saving the white child’s life, all else being equal? Ought we then not divert precious funds to those most in need when we can save white rich kids who will live long, prosper, and have ipods?

If a corporation has dumped toxic waste in the black kid’s neighborhood, and the baby’s life expectancy is now 30% lower than the white kid’s, is saving the black kid now worth 30% less than saving the white kid?

If Herod has ordered that all male babies in a given city be slain, so their life expectancy is on average only 3 days, can we say that saving one from drowning is an almost worthless investment?

“If the life expectancy of a black child in the inner city is say, 10% less than that of a white baby in a wealthy suburb, is saving the black child’s life worth 10% less than saving the white child’s life, all else being equal? Ought we then not divert precious funds to those most in need when we can save white rich kids who will live long, prosper, and have ipods?”

You’ve got it backwards. The fact that the black child’s life expectancy is lower means that the black child is the one we can help using money.

“If Herod has ordered that all male babies in a given city be slain, so their life expectancy is on average only 3 days, can we say that saving one from drowning is an almost worthless investment?”

That is correct. Although killing Herod would be a very worthwhile investment – next to even a low probability of killing Herod, saving babies from drowning would be total waste of time and resources. Do you disagree with that?

What you’re missing, Phil, is that we’re looking at both ends of the equation: what can we do to make someone’s life better, and what can’t we do? What are we saving them from, and what are we saving them for? You seem to think we’re looking only at the latter, but I’m not sure why given that the original topic is “saving lives in Africa.” Leaving out either perspective seems narrow minded.

I call our approach “the triage approach” because it’s based on the practice of doctors in wartime: treat people who need help AND can benefit from help. More on this here.

Hi guys,

This looks interesting…came over from NYTimes and am just poking around. The perfectionist in me can’t help but complain that the line colors change from the top to bottom graph. Your points are easier to follow if the colors are consistent. OK, back to browsing your site…

Dear Colleagues

I believe this is a very important piece of dialog … but also one that few people will really understand, and where there will be constrant disagreement. Saving a life is therefore not going to be an adequate metric for international relief and development sector performance.

I was surprised that child mortality related to nutrition was not apparent in your analysis. The one liner “3,000 children die every day in Africa from malaria” and the one liner “30,000 children die every day in Africa from all causes” sticks in my mind. As I understand it, poor nutrition and dangerous water are the biggest component of the big number.

Analysis of relief and development sector performance requires multi-variate analysis, which is complex and not easy to interpret … but measurement of cost effectiveness can be achieved in a useful way by looking at progress at the community level rather than trying to measure only within the organization or the project. Community level metrics are rarely compiled, but when they are, there is a clarity about how much money is spent, what it is used for, and the changes that are a result.

Analysis can also be helped by using the concept of “standards” … similar to the standard cost accounting metodology used in corporate performance analysis.

In the field of relief and development metrics there needs to be clear info about costs … about activities undertaken … about the results of the activities … and about the impact and value of the activities.

For cash sustainability the value has to be capable of monetisation in an amount greater than the cash outlays.

We see “Development” as much more than simply saving a life … it is also setting the stage for that life to have some happiness and to have some opportunity and to be of some value.

Most of the funds disbursed over the past 40 plus years through the international relief and development industry have not produced very much of sustainable progress.

Though saving a life justifies any amount of spending … it does not in any way address the question of what is the best way to spend the available money and get sustainable progress.

The vast (but insufficient) amounts of money spent on health initiatives have not been matched by initiatives in education, in infrastructure, in productive investment and job creation, in governance. A one leg stool does not stand up. One initiative development does not stand up either.

Sincerely

Peter Burgess

The Tr-Ac-Net Organization

Peter: I agree that we were a bit narrow in our “saving lives” goal. It’s a goal that has a certain philosophical appeal (some people are happy to save people from death, even if they have other problems in their lives) and that we thought we could tackle in our first year. But for the next round, we want to – and will – look at quality of life more broadly. I expect nutrition to be near the top of our list.

You’ve also emailed us; we’ll be in touch soon.

Comments are closed.