The Money for Good study’s headline finding is that “few donors do research before they give, and those that do look to the nonprofit itself to provide simple information about efficiency and effectiveness.”

That conclusion syncs up with our own experience talking to donors, but we aren’t discouraged by the results. That’s because where the Money for Good study answered the question “how do most donors behave?” we’re interested in answering a different question: is there a market for giving based on evidence of impact and how big is that market?

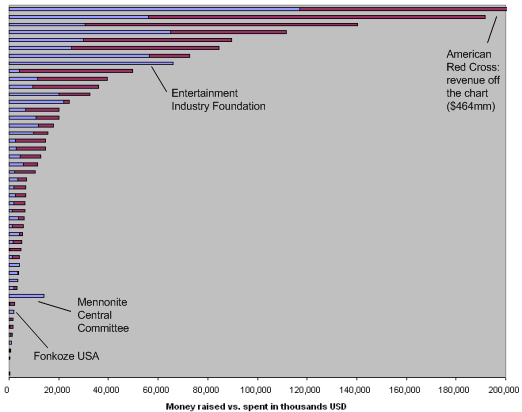

Hope Consulting shared their raw survey data with us, and we’ve done a rough estimate of the size of the potential “GiveWell market” by extrapolating the percentages in the survey to the size of the overall giving market. We estimate:

- $4.1 billion from donors who report having done research to compare and evaluate multiple organizations (as opposed to researching a single organization or researching how much to give).

- $3.8 billion if we further narrow the above set by looking at what factors are important to them, and eliminate any donors that rank what we consider “factors irrelevant to impact” (e.g., “ability to get involved with the organization” or “public recognition of my donation”) higher than what we consider “factors relevant to impact” (e.g., “organizational effectiveness”)

- $554 million from donors who both did research to compare organizations (i.e., fit in the first group above) and reported that “amount of good organization is accomplish” was the most important piece of information sought in their research.

We still don’t have a great sense of the potential market size for GiveWell-style research, but it certainly hasn’t been established that the market is small.

Ultimately, we think it’s important to take the study’s conclusions with a grain of salt. If you polled all TV watchers on what they want, you’d conclude that only a very small percentage want something like The Wire, yet that show wasn’t exactly a failure. In fact, for most successful businesses I can think of, it’s still the case that most people aren’t customers of them.

Our goal isn’t to create a product that the majority of people like; it’s to create a product that some minority market loves. From what we’re seeing now, it’s still possible that the minority of donors interested in impact-focused research is quite large.