A single-parent family of three in New York, making $8000 per year, makes under half the income level of the Federal poverty line and qualifies for food stamps, TANF (direct cash benefits) and Medicaid. (Details at our guide to U.S. public assistance)

And yet, at $2,667 per person per year, this family is wealthier than 70% of the people in the world. (See the Global Rich List calculator as well as the Giving What We Can version, which may be using more up-to-date data.)

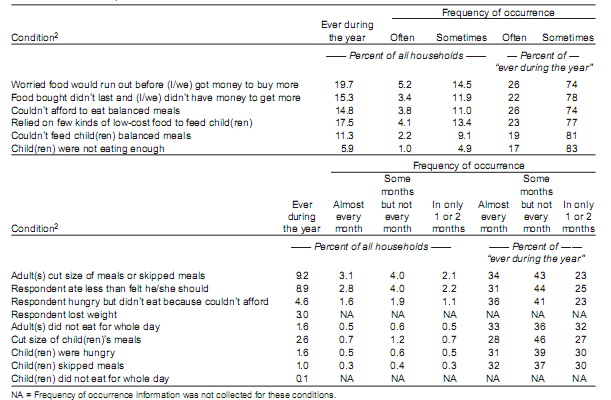

In the poorest parts of the world, fewer than half have access to a latrine or toilet; only 17% own a television; and 19-45% lack access to a reliable source of clean water. In the U.S., practically everyone has all three. (Details.) As we wrote yesterday, the two areas have completely different concepts of “hunger.” And finally, while anyone in the U.S. can ultimately be served in an emergency room, people across the world die or suffer from health conditions for which proven solutions exist.

In the U.S., helping the less fortunate usually means tackling a thorny “equality of opportunity” problem such as improving education or helping struggling adults to find and retain jobs. These problems have a long history of failure and few proven approaches to them. By contrast, helping people overseas can mean delivering something as proven and life-changing as a bednet or tuberculosis treatment.

Hopefully, these observations give some context on why a charitable dollar goes so much further overseas. If you are looking to use your wealth to help those less fortunate, we believe it’s hard to argue the case for U.S. as opposed to international charity, unless you believe that American lives are orders of magnitude more valuable.