We are concerned about the way repayment rates are often reported. We’ve written about this issue before, arguing that different delinquency indicators can easily be misleading and pointing to one example we found where a microfinance institution’s reported repayment rate substantially obscures the portion of its borrowers that have repaid loans.

Following the links from David Roodman’s recent post about Richard Rosenberg, we found another paper Mr. Rosenberg authored making all the same points, much better than we did. The paper is Richard Rosenberg’s. “Measuring microcredit delinquency: ratios can be harmful to your health.” CGAP Occasional Paper #3. 1999. Available online here (pdf).

Relevant quotes from Mr. Rosenberg’s paper

The importance of using the “right” delinquency measure:

MFIs use dozens of ratios to measure delinquency. Depending on which of them is being used, a “98 percent recovery rate” could describe a safe portfolio or one on the brink of meltdown. (Pg 1)

The measure we’ve been asking for seems to be equivalent to what he calls the “collection rate.”

Most of the discussion will be devoted to three broad types of delinquency indicators: (a) Collection rates measure amounts actually paid against amounts that have fallen due. (b) Arrears rates measure overdue amounts against total loan amounts. (c) Portfolio at risk rates measure the outstanding balance of loans that are not being paid on time against the outstanding balance of total loans. (Pg 2)

It’s essential to not only know which measure is being used, but precisely how an MFI calculates its version of the measure:

But the reader must be warned that there is no internationally consistent terminology for portfolio quality measures—for instance, what this paper calls a “collection rate” may be called a “recovery rate,” a “repayment rate,” or “loan recuperation” in other settings. No matter what name is used, the important point is that we can’t interpret what a measure is telling us unless we understand precisely the numerator and the denominator of the fraction. (Pg 2)

Mr. Rosenberg describes different tests to which MFIs should subject various delinquency measures to determine which is most appropriate. For GiveWell’s purposes, one of the key tests is the “smoke and mirrors” test:

Can the delinquency measure be made to look better through inappropriate rescheduling or refinancing of loans, or manipulation of accounting policies? This is our smoke and mirrors test. (Pg 3)

The practice of rescheduling and renegotiating loans:

When a borrower runs into repayment problems, an MFI will often renegotiate the loan, either rescheduling it (that is, stretching out its original payment terms) or refinancing it (that is, replacing it—even though the client hasn’t really repaid it—with a new loan to the same client). These practices complicate the process of using a collection rate to estimate an annual loan loss rate. Before exploring those complications and suggesting alternative solutions for dealing with them, the author needs to issue a warning: any reader looking for a perfect solution will be disappointed. The suggested approaches all have drawbacks. It is important to recognize that heavy use of rescheduling or refinancing can cloud the MFI’s ability to judge its loan loss rate. This is one of many reasons why renegotiation of problem loans should be kept to a minimum—some MFIs simply prohibit the practice. (Pg 10)

The strengths of PAR (“portfolio at risk”) as a measure:

The international standard for measuring bank loan delinquency is portfolio at risk (PAR). This measure compares apples with apples. Both the numerator and the denominator of the ratio are outstanding balances. The numerator is the unpaid balance of loans with late payments, while the denominator is the unpaid balance on all loans The PAR uses the same kind of denominator as an arrears rate, but its numerator captures all the amounts that are placed at increased risk by the delinquency. (Pg 13)

And its weaknesses:

Like many other delinquency measures, the PAR can be distorted by improper handling of renegotiated loans. MFIs sometimes reschedule—that is, amend the terms of—a problem loan, capitalizing unpaid interest and set- ting a new, longer repayment schedule. Or they may refinance a problem loan, issuing the client a new loan whose proceeds are used to pay off the old one. In both cases the delinquency is eliminated as a legal matter, but the resulting loan is clearly at higher risk than a normal loan. Thus a PAR report must age renegotiated loans separately, and provision such loans more aggressively. If this is not done, the PAR is subject to smoke and mirrors distortion: management can be tempted to give its portfolio an artificial facelift by inappropriate renegotiation. (Pg 16)

PAR can also be misleading in a situation where an MFI is growing rapidly (a key argument of our past posts):

Another potential distortion in PAR measures is worth mentioning. Arguably the PAR denominator should include only loans on which at least one payment has fallen due, so that late loans in the numerator are compared only to loans that have had a chance to be late. Nevertheless, it is customary to use the total outstanding loan balance for the denominator. The distortion involved is usually not large for MFIs, because the period before the first payment is a small fraction of the life of their loans. For instance, for a stable portfolio of loans paid in 16 weekly installments with no grace period, a PAR of 5.0 percent measured with the customary denominator (total outstanding portfolio) would rise only to 5.3 percent using the more precise denominator (excluding loans on which no payment has yet come due.) However, if a portfolio is growing very fast, or if there is a grace period or other long interval before the first payment is due, then the customary PAR denominator can seriously understate risk. Pg 17

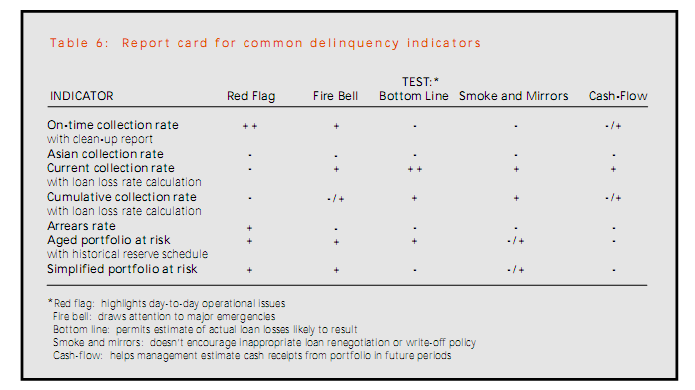

Table 6 on Pg 19 summarizes the strengths of weaknesses of different measures:

Why is this important?

Given how complicated this all is, we think that MFIs need to be clear and transparent about (a) which measures they use and (b) precisely how they calculate them.

However, this isn’t the case. For example, we aren’t confident that most MFIs normally report rescheduled and renegotiated loans as at-risk in PAR measures.

On the one hand, Commenter Ben writes, “Best practice is to treat all loans that have been rescheduled as PAR.” (This is consistent with MixMarket’s glossary, which indicates that, “[A PAR measure] also includes loans that have been restructured or rescheduled.”

Nevertheless, “best practice” may not correlate with “in practice.”

- This Kiva document (its “Partnership Application”) is explicit in the definition of PAR 30: “The value of loans outstanding that have one or more repayments past due more than 30 days. This includes the entire unpaid balance of the loan, including both past due and future installments, but not accrued interest or renegotiated loans.” (emphasis mine) Note that, to Kiva’s credit, it explicitly asks for renegotiated loans separately in the application.

- As Holden recently commented, “At least one MFI has indicated to us that it does not report [renegotiated loans in its PAR measures].”

The definition you read today isn’t necessarily the one that MFIs are using.

What measure do we use and why?

We’ve written before that our preferred measure is what the paper discussed above calls the collection rate. While the collection rate measure fails to provide a warning to MFIs that their portfolio is in danger, it is the strongest on Mr. Rosenberg’s “Bottom-line” test because it simply and clearly measures failed repayments. It’s therefore less susceptible to obfuscation and manipulation.

For GiveWell’s purposes, we need a delinquency measure that most clearly reports borrowers’ situations. While PAR measures provide information, it’s clear that PAR measures are more valuable to evaluating the risk of an MFI’s portfolio, which while relevant is not our key concern.