We got more attention today than we can handle. We have a tremendous volume of questions, comments, concerns, and requests and it’s going to take us a while to dig through them. We have no customer service dept – it’s just me, Elie, and Teel – but we will get it done. So if you emailed us or commented on our blog and you’re wondering where we went, we’ll be responding to you as soon as is practical (should be within a week), and we appreciate your patience.

Highlights of what caused the ruckus:

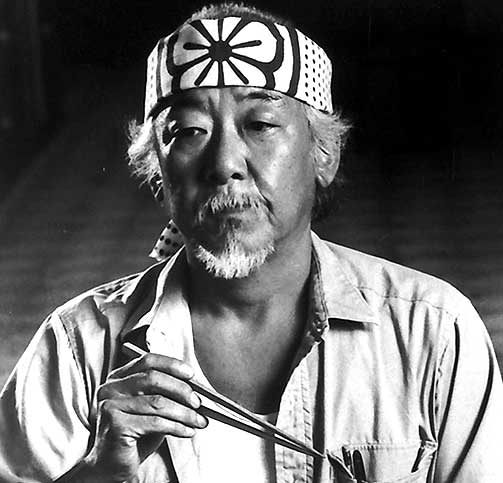

- New York Times feature that is currrently the 3rd most emailed story on NYT. Stephanie Strom did a great job turning our nerdy research project into a story that people want to read and pass on. That photo is so evil-looking that it’s already giving me nightmares.

- CNBC interview on Power Lunch. Apparently I messed up by putting my hands behind the chair. Sorry.

- Wall Street Journal article about taking charity evaluation beyond the Straw Ratio. This is a fantastically exciting article in that it’s directly taking on the difference between effectiveness and “low overhead.” Between it and the NYT, it’s a dark day for naive accounting metrics. Kudos to Rachel Silverman and Sally Beatty.

We recognized that donors are more likely to trust us for some decisions (comparing organizations with similar goals) than for others (for example, trying to compare the value of

We recognized that donors are more likely to trust us for some decisions (comparing organizations with similar goals) than for others (for example, trying to compare the value of  Regarding (1): Experience can be educational … or it can not be. It’s educational when it consists of trying something, learning whether it worked, and trying something else, all in an environment where “what works” is fairly stable. A highly experienced glovemaker will know all kinds of tricks of the trade and have all kinds of instincts that a young but “naturally talented” glovemaker doesn’t.

Regarding (1): Experience can be educational … or it can not be. It’s educational when it consists of trying something, learning whether it worked, and trying something else, all in an environment where “what works” is fairly stable. A highly experienced glovemaker will know all kinds of tricks of the trade and have all kinds of instincts that a young but “naturally talented” glovemaker doesn’t. Regarding (2): In most fields, “expert” doesn’t just mean “experienced” – it means “proven.” Tons of people have been investing their whole lives and are still dreadful at it, worse than a bright young 18-year-old would be. But Warren Buffett has a strong track record of investment success; he’s a True Expert in investing. On a smaller scale, your local doctor hopefully has a track record of helping people get better. OK, there’s no randomized-design evaluation of him, but we have a lot of independent information about how medical ailments progress if untreated, and the people your doctor treats get better instead. Unlike a Middle Ages leech supplier, your doctor is a True Expert in medicine.

Regarding (2): In most fields, “expert” doesn’t just mean “experienced” – it means “proven.” Tons of people have been investing their whole lives and are still dreadful at it, worse than a bright young 18-year-old would be. But Warren Buffett has a strong track record of investment success; he’s a True Expert in investing. On a smaller scale, your local doctor hopefully has a track record of helping people get better. OK, there’s no randomized-design evaluation of him, but we have a lot of independent information about how medical ailments progress if untreated, and the people your doctor treats get better instead. Unlike a Middle Ages leech supplier, your doctor is a True Expert in medicine. I’ll use the example of a typical college fraternity. Nominally, the fraternity has a mission, something about “upholding honor and serving the community” or something. Nominally, the President is the person most qualified to help the fraternity promote this mission, the Treasurer is the best person to keep the books, etc. But really? The President is the most popular guy. The Treasurer is ~4th-most popular. The guy who slept with the President’s girlfriend is at the bottom of the totem pole. Etc.

I’ll use the example of a typical college fraternity. Nominally, the fraternity has a mission, something about “upholding honor and serving the community” or something. Nominally, the President is the person most qualified to help the fraternity promote this mission, the Treasurer is the best person to keep the books, etc. But really? The President is the most popular guy. The Treasurer is ~4th-most popular. The guy who slept with the President’s girlfriend is at the bottom of the totem pole. Etc. I am proud to announce the winner of the 2007 Holden Award for Excellence in Imperfection. This award has a rich history dating back to 3 minutes ago. The rules are as follows:

I am proud to announce the winner of the 2007 Holden Award for Excellence in Imperfection. This award has a rich history dating back to 3 minutes ago. The rules are as follows: