GiveWell started in the hedge fund world (as a collaboration between coworkers), and our staff and board is heavy on for-profit experience. When we talk about metrics and dashboards, a lot of people assume we’re applying business concepts, and that we want to see charities run more like businesses. That isn’t true.

Do businesses conduct academic-style studies employing randomization and statistical significance tests to figure out how they’re doing? If any do, I doubt they’re very good ones. If you’re running a chain of pizza joints, you don’t need to know anything about statistics, and you can get by without much of a dashboard too. That’s because the single most important thing you need to measure – profit – is hitting you in the face every day. And most of the other things you need to measure take care of themselves too. It’s easy to know how much you’re paying delivery boys and how that impacts your bottom line – and if they slack off, you’ll be hearing about it from your consumers. No followup surveys necessary.

The more complicated things get, and the more difficult-to-observe things you have that might affect you in long-term and difficult-to-notice (but still important) ways, the more you need to audit. That’s why companies do it. But there’s no business whose operations are as difficult to understand – and whose outcomes are as difficult to measure – as even the simplest charity trying to fight poverty.

If a charity doesn’t follow up with its clients, it will never know whether its efforts are very successful, moderately successful, or entirely worthless. It will have no way of figuring out when the plan that made sense in its director’s head is falling short in reality. It could keep doing things that make logical sense, but don’t work at all, for hundreds of years – and never find out. None of that is true of any business.

If a charity doesn’t follow up with its clients, it will never know whether its efforts are very successful, moderately successful, or entirely worthless. It will have no way of figuring out when the plan that made sense in its director’s head is falling short in reality. It could keep doing things that make logical sense, but don’t work at all, for hundreds of years – and never find out. None of that is true of any business.

Reading fundraisers’ arguments for why their charities are good, I keep hearing things like “We’re very experienced,” “We’ve been around for a long time,” “We’re well recognized/well respected/well established.” These are all points that make perfect sense as praises for a for-profit business, and no sense as praises for a charity. Charities are mission-driven, not self-gain-driven. Continued existence is not evidence of success; fundraising excellence isn’t either. The fact is that without evaluation, a charity’s success is something no one can see.

Believe me, I know about the inherent limitations of measurement, and I know how expensive and annoying it is too. I don’t like to fill out a survey every time I blow my nose; if I were running a business, I wouldn’t want to be spending half our budget on figuring out whether our pizza really was the cause of improved customer happiness, or whether selection bias were involved. But if I were running a charity, I wouldn’t see a choice. It’s tough but true: unlike a business, a charity needs all that annoying stuff – or it’s working in the pitch dark.

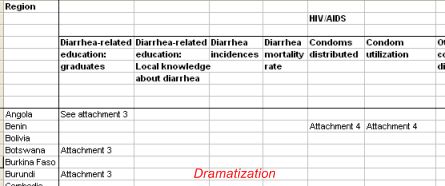

We’ve dubbed this app The Matrix, because its key feature is a gigantic matrix of regions and indicators – we want to know what each charity does and doesn’t have data on, in every region it works in. It’s visually gargantuan, but we’re not asking applicants to fill in statistics in the cells. All we’re asking is that they tell us what they do and don’t do – and what they do and don’t measure – in each of their regions.

We’ve dubbed this app The Matrix, because its key feature is a gigantic matrix of regions and indicators – we want to know what each charity does and doesn’t have data on, in every region it works in. It’s visually gargantuan, but we’re not asking applicants to fill in statistics in the cells. All we’re asking is that they tell us what they do and don’t do – and what they do and don’t measure – in each of their regions. I don’t hold small organizations, or simple organizations, to the same standard of measurement and organization. A bicycle doesn’t need a dashboard, because you can tell immediately if something’s wrong; unmetaphorically, if you work in one place, doing one thing, you can be part of the day-to-day activities and understand them intuitively, without ever measuring or documenting a thing. But for the life of me, I can’t understand how it’s possible to have an “intuitive” feel for your work when you’re trying to help thousands of different people, thousands of miles away, living in cultures and regions you didn’t grow up in and will never truly understand. It seems like the only way to have any idea of what’s going on is to collect an enormous quantity of facts and put great care into interpreting and organizing them. Elie and I recognize that we aren’t experienced in these matters … but the idea that an organization would take weeks to put together a summary of what it does and whether it works is just hard for us to swallow.

I don’t hold small organizations, or simple organizations, to the same standard of measurement and organization. A bicycle doesn’t need a dashboard, because you can tell immediately if something’s wrong; unmetaphorically, if you work in one place, doing one thing, you can be part of the day-to-day activities and understand them intuitively, without ever measuring or documenting a thing. But for the life of me, I can’t understand how it’s possible to have an “intuitive” feel for your work when you’re trying to help thousands of different people, thousands of miles away, living in cultures and regions you didn’t grow up in and will never truly understand. It seems like the only way to have any idea of what’s going on is to collect an enormous quantity of facts and put great care into interpreting and organizing them. Elie and I recognize that we aren’t experienced in these matters … but the idea that an organization would take weeks to put together a summary of what it does and whether it works is just hard for us to swallow. When I first heard about microfinance, everywhere I turned was a story like

When I first heard about microfinance, everywhere I turned was a story like

Most of the organizations we’re covering in Africa don’t just do one thing, they do many. I want to get a picture of what the organization as a whole is trying to accomplish (my benchmark is to understand 80% of programs) and the evidence that supports the effectiveness of those programs. I can’t think of any other way to evaluate the efficacy of an organization. It sounds like Holden is worried that asking for 80% is going to be too hard on the charities we’re evaluating. Too hard to explain 80% of what you do? How could that be? If you can’t explain 80% of what you do relatively easily, then there’s just no way that your organization is running effectively. The organizations we fund have to be able to do that.

Most of the organizations we’re covering in Africa don’t just do one thing, they do many. I want to get a picture of what the organization as a whole is trying to accomplish (my benchmark is to understand 80% of programs) and the evidence that supports the effectiveness of those programs. I can’t think of any other way to evaluate the efficacy of an organization. It sounds like Holden is worried that asking for 80% is going to be too hard on the charities we’re evaluating. Too hard to explain 80% of what you do? How could that be? If you can’t explain 80% of what you do relatively easily, then there’s just no way that your organization is running effectively. The organizations we fund have to be able to do that. When a charity does a million things in a million places, it’s futile to try to understand all of it, or even 80%. Speaking very practically, we’ll be taxing the heck out of their development officers, asking for so much information – to say nothing of what we’ll be doing to ourselves. And who cares what all their programs are, anyway? We all know that funders have a tendency to impose their priorities on others. So an org is doing an AIDS program in Kenya because some foundation made them back when AIDS was hip. What does that tell us about the organization’s approach, effectiveness, and more importantly, what they’re going to do with future funds?

When a charity does a million things in a million places, it’s futile to try to understand all of it, or even 80%. Speaking very practically, we’ll be taxing the heck out of their development officers, asking for so much information – to say nothing of what we’ll be doing to ourselves. And who cares what all their programs are, anyway? We all know that funders have a tendency to impose their priorities on others. So an org is doing an AIDS program in Kenya because some foundation made them back when AIDS was hip. What does that tell us about the organization’s approach, effectiveness, and more importantly, what they’re going to do with future funds?