Do any charities know what they’re doing?

We think so. In fact, we’re banking on it. GiveWell’s mission is to help steer capital and foster dialogue, and that’s it. We plan to give grants the same way we’ve given our personal donations: look for charities that already have proven, effective, scalable ways of helping people – charities that already know what they’re doing – and give them money. No consulting, no expertise, no program development, and no restrictions. Money.

We think so. In fact, we’re banking on it. GiveWell’s mission is to help steer capital and foster dialogue, and that’s it. We plan to give grants the same way we’ve given our personal donations: look for charities that already have proven, effective, scalable ways of helping people – charities that already know what they’re doing – and give them money. No consulting, no expertise, no program development, and no restrictions. Money.

For-profit sector readers are probably bored right now and wondering whether I’m going to say anything, but I bet the same isn’t true of nonprofit sector readers. From everything I’ve seen, our model of grantmaking is the exception, not the rule. Foundations don’t fund charities, they fund projects; they design programs and agendas, then look for organizations that fit into them; they design project-specific budgets, then make sure each of “their” dollars goes where it’s supposed to.

Part of it may be that foundations consider themselves experts in their fields, and they think they know more than the charities they fund. And they might be right … but that isn’t how we think of ourselves. We have a lot of options, so we demand a ton of information from charities, and we demand that they engage our questions and suggestions intelligently – but in the end, they know way more about their work than we do, and they should be the ones to decide how they do it. The donor’s role is to fund it.

Part of it may be that foundations consider themselves experts in their fields, and they think they know more than the charities they fund. And they might be right … but that isn’t how we think of ourselves. We have a lot of options, so we demand a ton of information from charities, and we demand that they engage our questions and suggestions intelligently – but in the end, they know way more about their work than we do, and they should be the ones to decide how they do it. The donor’s role is to fund it.

It seems clear to me that this is would be a disastrous strategy if we didn’t pick our charities carefully. Hey – that’s exactly how it works today, with the lion’s share of charitable capital coming from people who have no access to good information (though at least they can get irrelevant financial data and nonsensical metrics).

But imagine if we actually put in the due diligence, and find the charities that already have smart, experienced, passionate people with proven, effective, scalable methods for helping people. Imagine if we find the organizations that have it all except money. At that point, it’s moot how much of our dollar is going to “overhead,” or anything else – sometimes overhead is necessary and sometimes it isn’t, and good people will make those decisions better than we can. At that point, it’s unnecessary for us to “keep the charities in line,” because they’ll keep themselves in line or lose next time around. Accountability, transparency, and competition are harsher taskmasters than any contract can be.

But imagine if we actually put in the due diligence, and find the charities that already have smart, experienced, passionate people with proven, effective, scalable methods for helping people. Imagine if we find the organizations that have it all except money. At that point, it’s moot how much of our dollar is going to “overhead,” or anything else – sometimes overhead is necessary and sometimes it isn’t, and good people will make those decisions better than we can. At that point, it’s unnecessary for us to “keep the charities in line,” because they’ll keep themselves in line or lose next time around. Accountability, transparency, and competition are harsher taskmasters than any contract can be.

When we find what we’re looking for, we’re looking at an alley-oop … all we have to do is throw them the ball. That’s going to be easier and more effective than doing the driving ourselves.

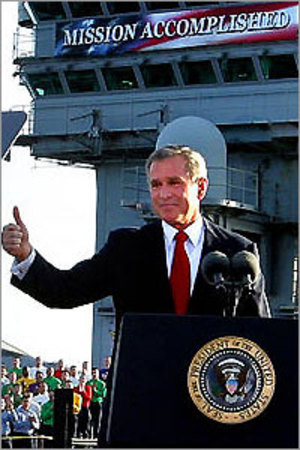

To be clear, I think NetSquared is an exciting idea. But where I come from, people celebrate a new client the day the client signs, not the day they decide to call the client and see if they’re interested. “Great research projects” refers to ideas that have been studied and stress-tested to death and produced returns, not to the ideas we had in this morning’s meeting. So as I’ve made clear, I’ve been pretty surprised by the extent to which people have called paragraphs on a screen “great projects,” and pointed to a “success” and “watershed event” where I saw an online poll that hadn’t even been tallied yet.

To be clear, I think NetSquared is an exciting idea. But where I come from, people celebrate a new client the day the client signs, not the day they decide to call the client and see if they’re interested. “Great research projects” refers to ideas that have been studied and stress-tested to death and produced returns, not to the ideas we had in this morning’s meeting. So as I’ve made clear, I’ve been pretty surprised by the extent to which people have called paragraphs on a screen “great projects,” and pointed to a “success” and “watershed event” where I saw an online poll that hadn’t even been tallied yet. Our fundraising efforts have started, and dang, do I hate asking for money. For three years, I’ve had way more income than I can spend, and I’ve rarely had to ask anyone for anything. That’s a nice position to be in. This – especially for an abrasive guy like me – is tough.

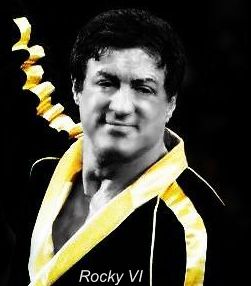

Our fundraising efforts have started, and dang, do I hate asking for money. For three years, I’ve had way more income than I can spend, and I’ve rarely had to ask anyone for anything. That’s a nice position to be in. This – especially for an abrasive guy like me – is tough. That’s why you should be concerned that philanthropy is currently seen as something to do with the “second half” of your life. “Second half” here isn’t just chronological – it’s referring to the half that specifically isn’t where the philanthropist made their name. The second half is the half that lacks risk, accountability, and the people who keep one honest (a set of factors collectively known as the “eye of the tiger”). All the great foundations today are following the orders of people who’ve made their fortune doing something else, and who no longer have to consider any criticism they don’t care for. I have to believe that matters, no matter how good their intentions.

That’s why you should be concerned that philanthropy is currently seen as something to do with the “second half” of your life. “Second half” here isn’t just chronological – it’s referring to the half that specifically isn’t where the philanthropist made their name. The second half is the half that lacks risk, accountability, and the people who keep one honest (a set of factors collectively known as the “eye of the tiger”). All the great foundations today are following the orders of people who’ve made their fortune doing something else, and who no longer have to consider any criticism they don’t care for. I have to believe that matters, no matter how good their intentions.  In addition to ~20 charity/philanthropy/social-goodliness blogs, I read one blog,

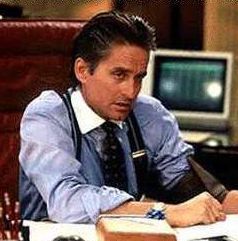

In addition to ~20 charity/philanthropy/social-goodliness blogs, I read one blog,  The thing is, in the business world it’s obvious to everyone that good isn’t good enough. You need to be the BEST, within your area, or else capital is better spent on your competitors – and you’re going to go under. But I don’t see why this is any less true of the nonprofit sector – all of it except the part about going under. Right now, there’s no mechanism for charitable capital (donations from individuals) to flow to where it’s best used, and that means no mechanism for inferior charities to go under, and THAT means no constant pressure to get better. That’s what we’re trying to change, because we think the people served by charities deserve the same relentless improvement and scrutiny that the people served by businesses benefit from.

The thing is, in the business world it’s obvious to everyone that good isn’t good enough. You need to be the BEST, within your area, or else capital is better spent on your competitors – and you’re going to go under. But I don’t see why this is any less true of the nonprofit sector – all of it except the part about going under. Right now, there’s no mechanism for charitable capital (donations from individuals) to flow to where it’s best used, and that means no mechanism for inferior charities to go under, and THAT means no constant pressure to get better. That’s what we’re trying to change, because we think the people served by charities deserve the same relentless improvement and scrutiny that the people served by businesses benefit from. Over 150 projects have been submitted for the NetSquared conference at the end of May, and only 20 will get to go. The winners will be determined by an online vote, open until this Saturday afternoon … and you know what that means:

Over 150 projects have been submitted for the NetSquared conference at the end of May, and only 20 will get to go. The winners will be determined by an online vote, open until this Saturday afternoon … and you know what that means: This has been our goal since last August, but we have come a long way in terms of strategy. Originally, our strategy was to do research on a part-time/”hobby” basis, and slap it all on a public website. As we discovered just how much there is to find, we investigated the idea of operating like Wikipedia: putting a lot of work into a basic structure that would allow thousands or millions of people to build the project up with their small contributions. But as we realized just how complex these problems are, and just how hard it is to find any useful information (and how useful it is to have large donations to use as leverage), we concluded that there’s really only one strategy that will achieve our goal well. That strategy is to create The Clear Fund: the world’s first charitable grantmaker whose reason for existence is to make its decisions accessible, useful, usable, and criticizable for all.

This has been our goal since last August, but we have come a long way in terms of strategy. Originally, our strategy was to do research on a part-time/”hobby” basis, and slap it all on a public website. As we discovered just how much there is to find, we investigated the idea of operating like Wikipedia: putting a lot of work into a basic structure that would allow thousands or millions of people to build the project up with their small contributions. But as we realized just how complex these problems are, and just how hard it is to find any useful information (and how useful it is to have large donations to use as leverage), we concluded that there’s really only one strategy that will achieve our goal well. That strategy is to create The Clear Fund: the world’s first charitable grantmaker whose reason for existence is to make its decisions accessible, useful, usable, and criticizable for all.