Background

Over the past 3 years, VillageReach has received over $2 million as a direct result of our recommendation. VillageReach put these funds towards its work to scale up its health logistics program, which it implemented as a pilot project in one province in Mozambique between 2002 and 2007, to the rest of the country. A core part of our research process is following the progress of charities to which GiveWell directs a significant amount of funding, and we’ve been following and reporting on VillageReach’s progress.

In addition to following VillageReach’s progress scaling up its program, we’ve recently been reassessing the evidence of the effectiveness of VillageReach’s pilot project. We’ve done this for two reasons. First, when we first encountered VillageReach, in 2009, GiveWell was a younger organization with a less developed research process. We believe that our approach for evaluating organizations has significantly improved and we wanted to see how VillageReach’s evidence would stack up given our current approach. Second, in its scale-up work, new data has become available that is relevant to our assessment of whether the pilot project was successful. GiveWell is now better than it was at understanding the extent to which it, or anyone, can draw conclusions from these sorts of impact evaluations.

In the case of the VillageReach evaluation, while we do not have facts to demonstrate otherwise, we now understand it is possible that factors other than VillageReach’s program might have contributed to the increase in coverage rate. As a result, we have moderated the confidence we had earlier in the extent to which VillageReach’s program was responsible for the increase in coverage rates.

This has major implications for our view of VillageReach, as compared to our current top charities (AMF and SCI), as a giving opportunity. We feel that within the framework of “delivering proven, cost-effective interventions to improve health,” AMF and SCI are solidly better giving opportunities than VillageReach (both now and at the time when we recommended VillageReach). Given the information we have, we see less room for doubt in the cases for AMF’s and SCI’s impact than in the case for VillageReach’s.

That said, we continue to view VillageReach as a highly transparent “learning organization” (capable of conducting its activities in a way that can lead to learning). Over the past few years, VillageReach has provided us with the source data behind its evaluations enabling us to do our own in depth analysis and draw our own conclusions. That work has contributed to our own growing ability to evaluate impact evaluations and determine the level of reliance that can be placed on them. We will be talking with VillageReach about how more funding could contribute to more experimentation and learning, and we will likely be interested in recommending such funding – to encourage such outstanding transparency and accountability, and learn more in the future.

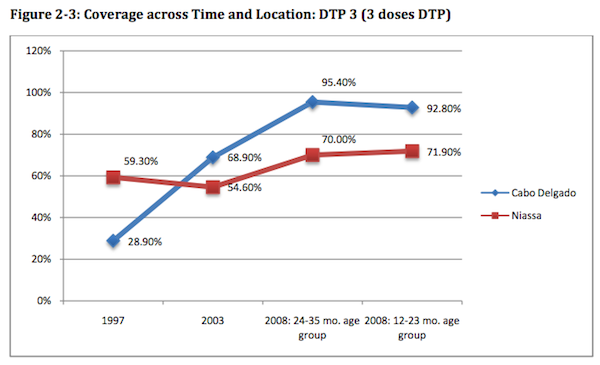

In our July 2009 review of VillageReach, we attributed an increase in vaccination rates in Cabo Delgado to VillageReach’s program.

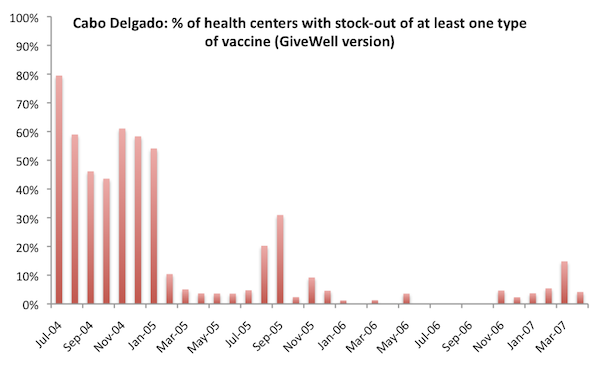

Two factors carried substantial weight in our view: (a) drops in the “stockout rate” of vaccines (i.e., the percentage of clinics that did not have all basic vaccine types available, see chart below) and (b) VillageReach’s report that other NGOs were unlikely to have contributed to the increase because they were not very involved with immunization activities during the 2002-2007 period.

In March 2012, we published a re-analysis that somewhat changed the picture presented by these charts. In it, the change in immunization coverage appears more similar between Cabo Delgado and Niassa (though quite different from the other provinces in Mozambique); in addition, some of the “low stockouts” period in the first chart turns out to be a period in which there was substantial missing data (it still appears that stockouts were, in fact, low during this period, so this is something of a minor change, but it still presents a different picture from how we interpreted the data previously).

Since we first reviewed VillageReach in 2009, our understanding of international aid generally has improved, and we now have more context for alternative, non-VillageReach factors that could have led to the increase in immunization. For example, in other charity examinations, there have been cases in which we noted that the charity’s entry into an area appeared to coincide with a generally higher level of interest in the charity’s sector on the part of the local government. We sought to understand the extent to which there may be an alternate explanation for the improvements that were concurrent with VillageReach’s activities.

We have not found any evidence that activities by other NGOs (i.e., non-governmental organizations) contributed to the increase in coverage rates, but reflecting on that question led us to focus on whether activities by governmental aid organizations (multilaterals and bilaterals) could have contributed to the increase in coverage rates. To answer this question we contacted and spoke with groups familiar with Mozambique’s immunization program during the 2002-2007 period. We spoke with Karin Turner, Deputy Director, Health Systems for USAID Mozambique (as well as other staff in that office) and Dr. Manuel Novela, a WHO EPI (Expanded Program on Immunization) Specialist for Mozambique.

Our understanding from these conversations is that:

- As an alternative to prior separate donor-direct funding mechanisms, major international donors started contributing to “common funds” around the year 2000. Common funds aimed to provide general operating support (and greater decision making autonomy) to developing countries’ ministries of health. When we spoke with USAID’s Mozambique office in April, reprensentatives told us that it recalled that Cabo Delgado and Niassa, the two provinces in Mozambique which experienced the largest increases in immunization rates between 2003 and 2008, used a larger proportion of their common fund funds on immunization-related activities than other provinces. We recently reached out to USAID in Mozambique to confirm this and we have not yet received an answer. Unfortunately, we have also not been able to track down data on how common funds were spent. [UPDATE September 10, 2012: Our current understanding is that USAID believes Niassa and Cabo Delgado had the ability to focus common funds on vaccination, but that it does not know whether this was done.]

- In the early 2000s, other funders became interested in supporting Northern Mozambique (of which Niassa and Cabo Delgado are a part), specifically. According to USAID, Irish Aid and the World Bank provided increased support for immunization activities to Niassa during the 2000s. We have no evidence, however, of additional funders for immunization activities in Cabo Delgado.

At this point we feel that the fall in stockouts and rise in immunization rates observed in Cabo Delgado could be attributed to VillageReach’s activities (and the improvement in Niassa attributed to the activities of Irish Aid and the World Bank discussed above), but it is possible to speculate that the improvements in both provinces were driven by another factor (perhaps the allocation of common funds) that we do not have full context on. The fact that Niassa, a neighboring province, experienced a large rise in immunization rates (although not to the 90%+ range seen in Cabo Delgado) over the same period (see chart above) raises the possibility (from our perspective) that non-VillageReach factors contributed to the rise in immunization rates in Cabo Delgado (although it is also possible to speculate that Irish Aid/World Bank funds spent in Niassa increased coverage rates there while the VillageReach program in Cabo Delgado was responsible for the increases in that province). We have also not looked into immunization funding in other (i.e., non-Niassa or Cabo Delgado) provinces over this period. Were we to find evidence of increased funding for immunization without commensurate increases in immunization coverage, it would reduce our assessment of the probability that government funds were responsible for the increase in Cabo Delgado.

VillageReach’s perspective

We asked Leah Hasselback, VillageReach’s Mozambique Country Director, about possible additional factors. She told us that in completing its evaluation of the pilot project, VillageReach had spoken with WHO as well as with bilateral donors, and that no one had mentioned Cabo Delgado’s using common funds for immunization or additional immunization-specific funding for Cabo Delgado. Note that VillageReach’s assessment of other factors was completed after the fact.

Additional Data

VillageReach exited Cabo Delgado in 2007. Recently, two different data sets have become available on immunization coverage in the province in 2010-2011. The first is a survey conducted by VillageReach, and the second is the DHS report for 2011. The key question we asked when examining these was whether they demonstrate a worsening of immunization coverage relative to 2008; if immunization coverage had worsened in the years since VillageReach exited (during which time its distribution system was discontinued), this would provide some suggestive evidence for the importance of the VillageReach model.

The two data sets present different pictures. The VillageReach survey data shows different trends in different figures, but overall we feel it does not show worsening of immunization coverage. On the other hand, the DHS report does show signs of worsening in coverage. (Details in the footnote at the end of this post.)

VillageReach’s perspective

Leah Hasselback, VillageReach’s Country Director for Mozambique, notes several other factors occurring in Cabo Delgado between 2007 and 2010 may have caused immunization rates to stay higher:

- Mozambique introduced the pentavalent vaccine in November 2009. This vaccine, which includes 5 needed vaccines in one, was accompanied with significant vaccine-related promotion which also should have improved immunization rates.

- Cabo Delgado added 20 additional health centers between the end of VillageReach’s pilot project and its beginning its scale up work. During the entire period of the pilot project, Cabo Delgado added only 1 health center.

- There were immunization campaigns in 2008 that focused specifically on measles and polio.

- FDC, the local NGO with which VillageReach partnered during the pilot project, ran a social mobilization campaign in 2008-09 in a single district of Cabo Delgado.

Though its pilot project evaluation is the single best evaluation we have ever seen from a nonprofit evaluating its own programs (as opposed to academics running randomized controlled trials of aspects of an organization’s activities), and the evaluation is both thoughtful and self-critical, we still feel that there are too many unanswered (and perhaps unanswerable) questions about VillageReach’s impact to have strong confidence that it caused an increase in immunization rates.

This view has major implications for our view of VillageReach, as compared to our current top charities (AMF and SCI), as a giving opportunity. We feel that within the framework of “delivering proven, cost-effective interventions to improve health,” AMF and SCI are solidly better giving opportunities than VillageReach (both now or at the time when we recommended it). Given the information we have, we see less room for doubt in the cases for AMF’s and SCI’s impact than in the case for VillageReach’s.

On the other hand, we wish to emphasize another sense in which VillageReach was – and is – an outstanding giving opportunity. VillageReach is experimenting with a novel approach to health, collecting meaningful data that can lead to learning, and sharing what it finds – both the good and the bad – in a way that is likely to improve the knowledge and efficiency of aid as a whole. In this respect we see it as very unusual: most of the charities we’ve encountered seem to collect little meaningful data, are reluctant to share what they do have, and are especially reluctant to share anything that may call their impact into question.

Groups like VillageReach are creating a new dialogue around charitable giving, and it’s important to us that this type of behavior is supported. We want to encourage VillageReach and other groups to share information about how their programs are going, and we want to continue to see more experimentation and learning. So, we are seriously considering recommending donations to VillageReach, not despite the struggles it’s had but because it’s had these struggles and is being honest about them.

VillageReach has sent us a funding update, which we plan to review and share soon. We will also be writing more, in future posts, about what we’ve learned overall from the experience of working with VillageReach, and what we feel it says about our research process.

For the below analysis we relied on two studies conducted by VillageReach or contractors hired by VillageReach:

- A July 2008 survey of two groups of children in Cabo Delgado: children aged 12-23 months (likely vaccinated at the end and after the VR project, which ended in Feb-Apr 2007) and children aged 24-25 months (likely vaccinated during the project).

- An April 2010 survey of children 12-23 months of age. None of these children would have been vaccinated during the VillageReach pilot project.

There are three main indicators that VillageReach uses as numerators for the “vaccination coverage rate”:

- Fully vaccinated: child has received each of 8 vaccinations by the time of the survey (BCG, 3 x DTP, 3 x Polio, Measles). A vaccination is counted if either it is recorded on the child’s vaccination card (which are kept by parents) or if a caregiver states that the child received the vaccination.

- Fully immunized (either by time of survey or before 12 months of age): This is a stricter measure than “fully vaccinated.” In addition to having all the vaccinations, there are additional conditions which must be met:

- All vaccinations and timings must be verified on the child’s vaccination card (verbal confirmation by a caregiver is not valid).

- All 3 polio vaccinations must be received at least 28 days apart. Same for DTP vaccinations.

- Measles vaccination must be given after 9 months of age.

- DTP3: Received all 3 diptheria, pertussis, and tetanus vaccinations. Verification with the vaccination card is not needed.

In Cabo Delgado rates of “fully vaccinated” and DTP3 remained more or less constant in the 2008 and 2010 surveys:

- Fully vaccinated:

- 2008: 92.8% for 24-35 month olds and 87.8% for 12-23 months olds

- 2010: 89.1% (12-23 month olds)

- DTP3:

- 2008: 95.4% for 24-35 month olds and 92.8% for 12-23 months olds

- 2010: 91.9% (12-23 month olds)

It’s harder to interpret the fully immunized figures. The figure for this did fall between 2008 and 2010:

- Fully immunized at the time of the survey:

- 2008: 72.2% for 24-35 month olds and 73.0% for 12-23 months olds

- 2010: 57.9% or 48.8% (both numbers are given in the report; 48.8% is the one that is repeated in summary reports VillageReach has published)

- Fully immunized by 12 months of age:

- 2008: 54.9% for 24-35 month olds and 61.2% for 12-23 months olds

- 2010: 40.8%

The primary reasons that children failed to qualify as fully immunized in the 2010 survey do not appear to be issues that better vaccine logistics, the issue addressed by VillageReach’s program, would likely have addressed (these categories can overlap):

- 27% of the whole sample (i.e., at least half of those who didn’t qualify as fully immunized) received their measles vaccine before 9 months of age, up from 8% in the 2008 survey

- 19% of the sample got polio or DTP shots within 28 days of each other, up from 2% in 2008 survey

- Only 11.5% of the sample got a vaccination after 12 months of age

In this spreadsheet, we have compiled vaccination rate data from four national, high-quality surveys: 3 DHS surveys in 1997, 2003, and 2011, and a Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) from 2008. Note that only a subset of the children included in the 2008 survey were born in time to potentially directly benefit from VillageReach’s pilot project. With that caveat in mind, a few observations:

- DPT3 vaccination and fully vaccinated rates observed in Cabo Delgado in 2011 were substantially lower in 2011 than in 2008, while rates were found to have risen over that period in nearby provinces, including Niassa, the comparison province from VillageReach’s project evaluation.

- Vaccination rates for vaccines earlier in the vaccination series (such as DPT1, DPT2, and BCG) were found to be about the same or decreased only slightly from the 2008 to the 2011 surveys.

Sources:

- VillageReach’s 2008 Cabo Delgado vaccination survey (PDF).

- VillageReach’s 2010 Cabo Delgado vaccination survey (PDF).

- Summary presentation on 2010 Cabo Delgado vaccination survey (PDF).

- Multiple indicator cluster survey (2008) (PDF).

- Demographic and Health Survey (2011; preliminary report) (PDF).

- Recommended schedule for routine immunizations for children (PDF) from the World Health Organization.