We’ve recently been writing about the shortcomings of formal cost-effectiveness estimation (i.e., trying to estimate how much good, as measured in lives saved, DALYs or other units, is accomplished per dollar spent). After conceptually arguing that cost-effectiveness estimates can’t be taken literally when they are not robust, we found major problems in one of the most prominent sources of cost-effectiveness estimates for aid, and generalized from these problems to discuss major hurdles to usefulness faced by the endeavor of formal cost-effectiveness estimation.

Despite these misgivings, we would be determined to make cost-effectiveness estimates work, if we thought this were the only way to figure out how to allocate resources for maximal impact. But we don’t. This post argues that when information quality is poor, the best way to maximize cost-effectiveness is to examine charities from as many different angles as possible – looking for ways in which their stories can be checked against reality – and support the charities that have a combination of reasonably high estimated cost-effectiveness and maximally robust evidence. This is the approach GiveWell has taken since our inception, and it is more similar to investigative journalism or early-stage research (other domains in which people look for surprising but valid claims in low-information environments) than to formal estimation of numerical quantities.

The rest of this post

- Conceptually illustrates (using the mathematical framework laid out previously) the value of examining charities from different angles when seeking to maximize cost-effectiveness.

- Discusses how this conceptual approach matches the approach GiveWell has taken since inception.

I don’t wish to present this illustration either as official GiveWell analysis or as “the reason” that we believe what we do. This is more of an illustration/explication of my views than a justification; GiveWell has implicitly (and intuitively) operated consistent with the conclusions of this analysis, long before we had a way of formalizing these conclusions or the model behind them. Furthermore, while the conclusions are broadly shared by GiveWell staff, the formal illustration of them should only be attributed to me.

The model

Suppose that:

- Your prior over the “good accomplished per $1000 given to a charity” is normally distributed with mean 0 and standard deviation 1 (denoted from this point on as N(0,1)). Note that I’m not saying that you believe the average donation has zero effectiveness; I’m just denoting whatever you believe about the impact of your donations in units of standard deviations, such that 0 represents the impact your $1000 has when given to an “average” charity and 1 represents the impact your $1000 has when given to “a charity one standard deviation better than average” (top 16% of charities).

- You are considering a particular charity, and your back-of-the-envelope initial estimate of the good accomplished by $1000 given to this charity is represented by X. It is a very rough estimate and could easily be completely wrong: specifically, it has a normally distributed “estimate error” with mean 0 (the estimate is as likely to be too optimistic as too pessimistic) and standard deviation X (so 16% of the time, the actual impact of your $1000 will be 0 or “average”).* Thus, your estimate is denoted as N(X,X).

The implications

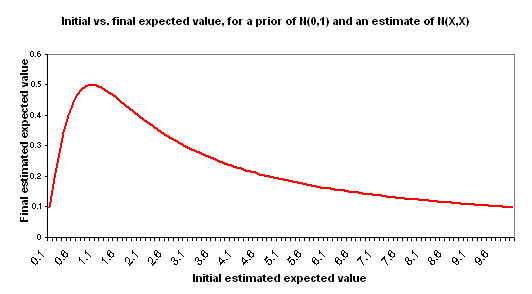

I use “initial estimate” to refer to the formal cost-effectiveness estimate you create for a charity – along the lines of the DCP2 estimates or Back of the Envelope Guide estimates. I use “final estimate” to refer to the cost-effectiveness you should expect, after considering your initial estimate and making adjustments for the key other factors: your prior distribution and the “estimate error” variance around the initial estimate. The following chart illustrates the relationship between your initial estimate and final estimate based on the above assumptions.

This is in some ways a counterintuitive result. A couple of ways of thinking about it:

- Informally: estimates that are “too high,” to the point where they go beyond what seems easily plausible, seem – by this very fact – more uncertain and more likely to have something wrong with them. Again, this point applies to very rough back-of-the-envelope style estimates, not to more precise and consistently obtained estimates.

- Formally: in this model, the higher your estimate of cost-effectiveness goes, the higher the error around that estimate is (both are represented by X), and thus the less information is contained in this estimate in a way that is likely to shift you away from your prior. This will be an unreasonable model for some situations, but I believe it is a reasonable model when discussing very rough (“back-of-the-envelope” style) estimates of good accomplished by disparate charities. The key component of this model is that of holding the “probability that the right cost-effectiveness estimate is actually ‘zero’ [average]” constant. Thus, an estimate of 1 has a 67% confidence interval of 0-2; an estimate of 1000 has a 67% confidence interval of 0-2000; the former is a more concentrated probability distribution.

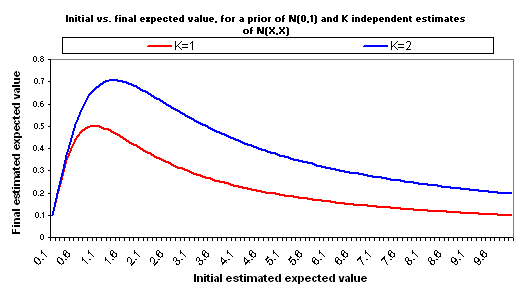

Now suppose that you make another, independent estimate of the good accomplished by your $1000, for the same charity. Suppose that this estimate is equally rough and comes to the same conclusion: it again has a value of X and a standard deviation of X. So you have two separate, independent “initial estimates” of good accomplished, and both are N(X,X). Properly combining these two estimates into one yields an estimate with the same average (X) but less “estimate error” (standard deviation = X/sqrt(2)). Now the relationship between X and adjusted expected value changes:

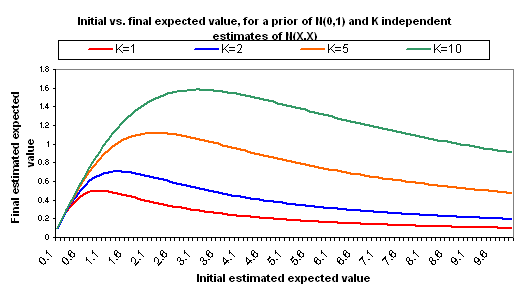

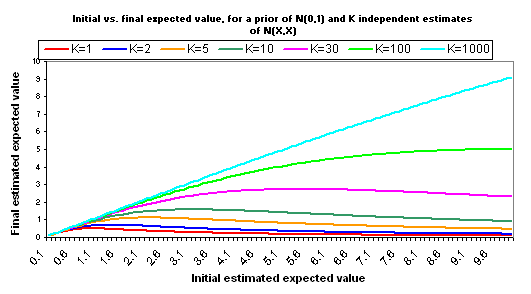

The following charts show what happens if you manage to collect even more independent cost-effectiveness estimates, each one as rough as the others, each one with the same midpoint as the others (i.e., each is N(X,X)).

A few other notes:

- The full calculations behind the above charts are available here (XLS). We also provide another Excel file that is identical except that it assumes a variance for each estimate of X/2, rather than X. This places “0” just inside your 95% confidence interval for the “correct” version of your estimate. While the inflection points are later and higher, the basic picture is the same.

- It is important to have a cost-effectiveness estimate. If the initial estimate is too low, then regardless of evidence quality, the charity isn’t a good one. In addition, very high initial estimates can imply higher potential gains to further investigation. However, “the higher the initial estimate of cost-effectiveness, the better” is not strictly true.

- Independence of estimates is key to the above analysis. In my view, different formal estimates of cost-effectiveness are likely to be very far from independent because they will tend to use the same background data and assumptions and will tend to make the same simplifications that are inherent to cost-effectiveness estimation (see previous discussion of these simplifications here and here).Instead, when I think about how to improve the robustness of evidence and thus reduce the variance of “estimate error,” I think about examining a charity from different angles – asking critical questions and looking for places where reality may or may not match the basic narrative being presented. As one collects more data points that support a charity’s basic narrative (and weren’t known to do so prior to investigation), the variance of the estimate falls, which is the same thing that happens when one collects more independent estimates. (Though it doesn’t fall as much with each new data point as it would with one of the idealized “fully independent cost-effectiveness estimates” discussed above.)

- The specific assumption of a normal distribution isn’t crucial to the above analysis. I believe (based mostly on a conversation with Dario Amodei) that for most commonly occurring distribution types, if you hold the “probability of 0 or less” constant, then as the midpoint of the “estimate/estimate error” distribution approaches infinity the distribution becomes approximately constant (and non-negligible) over the area where the prior probability is non-negligible, resulting in a negligible effect of the estimate on the prior.While other distributions may involve later/higher inflection points than normal distributions, the general point that there is a threshold past which higher initial estimates no longer translate to higher final estimates holds for many distributions.

number of people whose jobs produce the income necessary to give them and their families a relatively comfortable lifestyle (including health, nourishment, relatively clean and comfortable shelter, some leisure time, and some room in the budget for luxuries), but would have been unemployed or working completely non-sustaining jobs without the charity’s activities, per dollar per year. (Systematic differences in family size would complicate this.)

Early on, we weren’t sure of whether we would find good enough information to quantify these sorts of things. After some experience, we came to the view that most cost-effectiveness analysis in the world of charity is extraordinarily rough, and we then began using a threshold approach, preferring charities whose cost-effectiveness is above a certain level but not distinguishing past that level. This approach is conceptually in line with the above analysis.

It has been remarked that “GiveWell takes a deliberately critical stance when evaluating any intervention type or charity.” This is true, and in line with how the above analysis implies one should maximize cost-effectiveness. We generally investigate charities whose estimated cost-effectiveness is quite high in the scheme of things, and so for these charities the most important input into their actual cost-effectiveness is the robustness of their case and the number of factors in their favor. We critically examine these charities’ claims and look for places in which they may turn out not to match reality; when we investigate these and find confirmation rather than refutation of charities’ claims, we are finding new data points that support what they’re saying. We’re thus doing something conceptually similar to “increasing K” according to the model above. We’ve recently written about all the different angles we examine when strongly recommending a charity.

We hope that the content we’ve published over the years, including recent content on cost-effectiveness (see the first paragraph of this post), has made it clear why we think we are in fact in a low-information environment, and why, therefore, the best approach is the one we’ve taken, which is more similar to investigative journalism or early-stage research (other domains in which people look for surprising but valid claims in low-information environments) than to formal estimation of numerical quantities.

As long as the impacts of charities remain relatively poorly understood, we feel that focusing on robustness of evidence holds more promise than focusing on quantification of impact.

*This implies that the variance of your estimate error depends on the estimate itself. I think this is a reasonable thing to suppose in the scenario under discussion. Estimating cost-effectiveness for different charities is likely to involve using quite disparate frameworks, and the value of your estimate does contain information about the possible size of the estimate error. In our model, what stays constant across back-of-the-envelope estimates is the probability that the “right estimate” would be 0; this seems reasonable to me.