This Tactical Philanthropy post implies that the salient difference between DonorsChoose and Kiva is that DonorsChoose is more “authentic” in terms of connecting donors to projects. (Update: Sean points out in the comment below that most of the post I cited was a quote from a former DonorsChoose employee and doesn’t necessarily reflect TacticalPhilanthropy’s opinion.)

We think there’s another important difference. Kiva and DonorsChoose work on very different types of problems, that offer donors vastly different opportunities to cause significant impact. And if we had to pick one, we’d bet on Kiva as the better option if you want to change lives.

The problem of improving children’s education is far, far more difficult than most people suspect – for our most recent coverage, see our multi-part series on the recent Harlem Children’s Zone study, and how excited the academic community has been over a one-time and modest improvement. And DonorsChoose does not offer the chance to support any of the most promising and tested educational interventions, such as the creation of intensive charter schools. Funding DonorsChoose is making a bet that classroom materials are where it’s at, even when the teachers, school systems and children’s outside environments remain the same. As far as we know, there is zero evidence that improved school supplies have resulted in any measurable improvements in the U.S., and even in the developing world the proposition seems iffy.

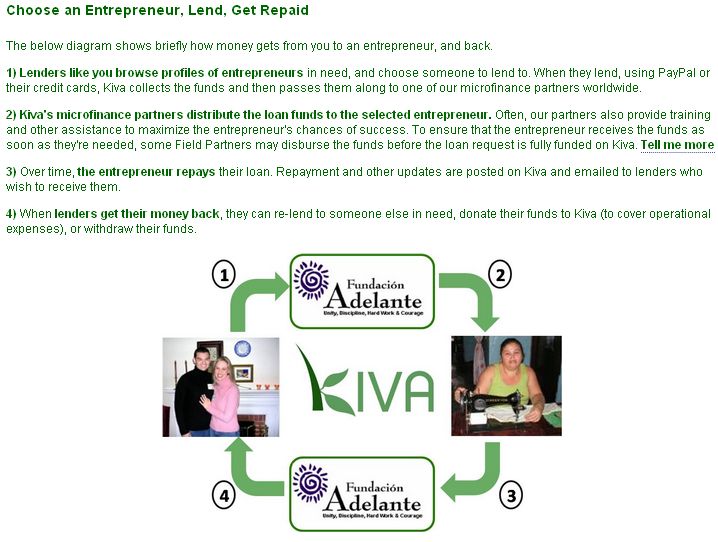

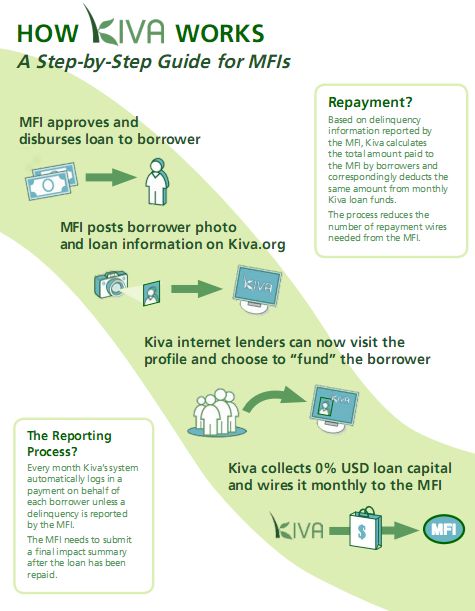

Funding Kiva, even if it doesn’t mean funding individuals, means funding microfinance charities. We are very ambivalent about microfinance; recent posts on this topic include questions about whether there’s any empirical support for microfinance charities’ claims and an interview with David Roodman about microfinance charity in which many unresolved questions come up. But the bottom line is that when you fund microfinance charities, your money ends up in the poorest parts of the world, and often (though we don’t know how often or how much) helps people there manage their volatile financial lives with credit, savings and other assistance.

(In fact, the way in which your money is most helpful may be by doing exactly what it has been criticized for doing – effectively funding partners’ other projects, such as savings vehicles, rather than the loans you see on your screen.)

Fund financial services in the poorest parts of the world, or fund an untested and low-intensity approach to a problem that higher-intensity programs have struggled with for decades. $900 can be five digital cameras for a classroom or a year’s income for 3 people.

That’s the decision as it looks to us, as we ask not “How can I make sure that I can see the exact person who’s getting my money?” but “How can my money accomplish as much good as possible?”

And on that note, we feel that our top-rated charities offer far better opportunities to improve lives than either, even if they can’t deliver the same emotional experience. As a donor, which would you rather have?