My last post summarized a very recent paper by Fryer and Dobbie, finding large gains for charter school students in the Harlem Children’s Zone. (You can get the study here (PDF)).

I believe that this paper is an unusually important one, for reasons that the paper itself lays out very well in the first couple of pages: a wealth of existing literature has found tiny, or zero, effects from attempts to improve educational outcomes. This is truly the first time I (and, apparently, the authors) have seen a rigorously demonstrated, very large effect on math performance for any education program at all.

This study does not show that improving educational outcomes is easy. It shows that it has been done in one case by one program.

The program in question is a charter school that is extremely selective and demanding in its teacher hiring (see pages 6-7 of the study), and involves highly extended school hours (see page 6). Other high-intensity charter schools with similar characteristics have long been suspected of achieving extraordinary results (see, for example, our analysis of the Knowledge is Power Program). This study is consistent with – but more rigorous than – existing evidence suggesting that such high-intensity charter schools can accomplish what no other educational program can.

Those who doubt the value of rigorous outcomes-based analysis should consider what it has yielded in this case. Instead of scattering support among a sea of plausible-sounding programs (each backed with vivid stories and pictures of selected children), donors – and governments – are now in a position where they can focus in on one approach far more promising than the others. They can work on scaling it up across the nation and investigate whether these encouraging effects persist, and just how far the achievement gap can be narrowed. As a donor, the choice is yours: support well-meaning approaches with dubious track records (tutoring, scholarships, summer school, extracurriculars, and more), or an approach that could be the key to huge gains in academic performance.

Reasons to be cautious

The result is exciting, but:

- This is only one study, and the sample size isn’t huge (especially for the most rigorous randomization-based analysis). It’s a very new study – not even peer-reviewed yet – and it hasn’t had much opportunity to be critiqued. We look forward to seeing both critiques of it and (if the consensus is that it’s worth replicating) the results of replications.

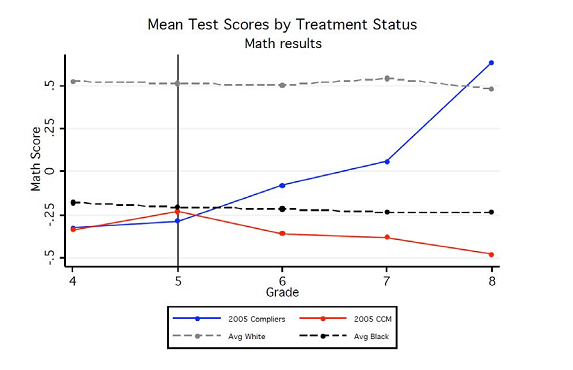

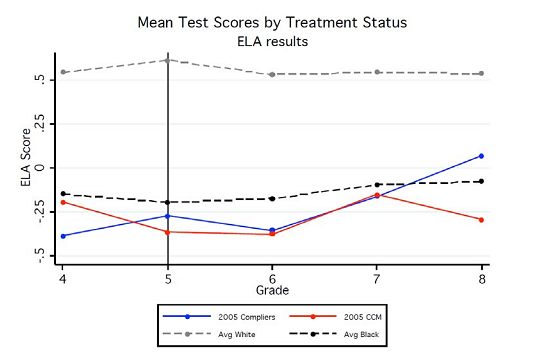

- Observed effects are primarily on math scores. Effects on reading are encouraging but smaller. Would this improved performance translate to improvements on all aspects of the achievement gap (either causally or because the higher test scores are symptomatic of a general improvement in students’ personal development)? We don’t know.

- Just because one program worked in one place at one time doesn’t mean funding can automatically translate to more of it. Success could be a function of hard-to-replace individuals, for example. Indeed, if the consensus is that this program “works,” figuring out what about it works and how it can be extended will be an enormous challenge in itself.

- With both David Brooks and President Obama lending their enthusiasm fairly recently, the worthy mission of replicating and evaluating this program could have all the funding it needs for the near future. Individual donors should bear this in mind.

Related posts: