There’s been a lot of excitement about microlending, especially since the 2006 Nobel Peace Prize created a wave of stories about it. The basic idea is to make loans to the destitute, helping them pull themselves out of poverty. The stories and the numbers floating around from fundraisers paint a picture that’s simply too good to be true (below) … we can’t authoritatively say that we have the real story, but I think I’m starting to understand the difference between these stories and how microlending actually helps people.

First, the good stuff.

The microlending you’ve heard of: beggars to billionaires, thousands of times a day

gramm

When I first heard about microfinance, everywhere I turned was a story like this one, or this one, or perhaps this one, or all these ones. (Dang. That was the easiest time I’ve ever had finding examples of anything.) Basic story: poor entrepreneur has a killer business model (OK, usually a fruit stand) that’s ready to expand, if only someone would lend the funds. In swoops a microlender; the entrepreneur borrows, expands the business, succeeds, and changes her life for good.

When I first heard about microfinance, everywhere I turned was a story like this one, or this one, or perhaps this one, or all these ones. (Dang. That was the easiest time I’ve ever had finding examples of anything.) Basic story: poor entrepreneur has a killer business model (OK, usually a fruit stand) that’s ready to expand, if only someone would lend the funds. In swoops a microlender; the entrepreneur borrows, expands the business, succeeds, and changes her life for good.

Now imagine how I felt after combining those basic stories with the aggregate numbers: repayment rates like 97%, on billions of dollars lent, with a typical loan being around $50 ??? So if each loan repaid is a person who has built a business and escaped poverty … then if I donate $50, it can be lent out repeatedly and help a family escape poverty every 6-12 months for the rest of eternity? And if Grameen Bank has lent out ~$5 billion … that’s … 100 million people lifted out of poverty forever?

I know what you’re thinking: “Sign me up! How could Holden doubt any of these claims?” Well, call me the Grinch, but here were a few things that bugged me:

1. If every loan were really going to expand a successful business, the lenders wouldn’t be nonprofits – they would for-profits, and Muhammad Yunus and his friends would all be katrillionaires. Oh, and poverty wouldn’t exist.

2. Expanding a business is going to involve serious risk, unless you’ve got new customers already lined up for miles. I know I never gave much thought to being an entrepreneur until I had some cash saved up … seems hard to believe that people living hand-to-mouth are all chomping at the bit to do it. This paper makes this general argument (hard to be an entrepreneur when you’re in poverty) a bit better than I just did.

3. Seriously … how many people do you know who could start a profitable business if you loaned them a million dollars?

But then again, if these people aren’t lifting themselves out of poverty, why and how are they borrowing money and paying it back? What’s really going on here?

The microlending that happens: credit as basic need

Here’s a paper you’ll be hearing more about in future posts. It’s a review of many studies of the actual impact of microfinance on poverty. Pages 17-20 describe one of the more rigorous attempts at this, and the debate over what it showed; the one thing all three of the studies agree on is that people with credit available had smoother consumption: “household consumption increased most during the lean Aus season, when the poor often go hungry.”

Here’s a paper you’ll be hearing more about in future posts. It’s a review of many studies of the actual impact of microfinance on poverty. Pages 17-20 describe one of the more rigorous attempts at this, and the debate over what it showed; the one thing all three of the studies agree on is that people with credit available had smoother consumption: “household consumption increased most during the lean Aus season, when the poor often go hungry.”

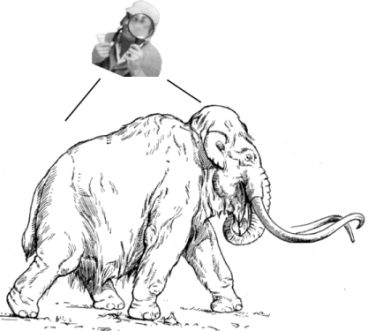

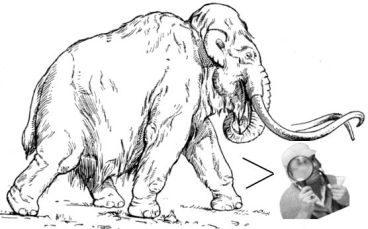

I don’t know about you, but I’ve always taken my ability to smooth consumption (saving, borrowing, etc.) so much for granted that it didn’t even occur to me what it would be like to live without it. But as this paper argues in great detail, the world’s poorest often are less badly hurting for food/medicine than they are for the most basic support networks and mechanisms we use to manage our lives. If your income is seasonal and you’ve got no bank, forget about starting a business – you can’t even plan for the next week.

In this context, giving loans isn’t about creating and expanding ventures, it’s about meeting a basic need that might be as vital as the classic food, water, and shelter: the ability to manage risk and plan for changes. Loans aren’t the key to ending poverty, but they’re one of many things that we have to make available.

So I’ve done it, I’ve killed Santa Claus. Microloans won’t end global warming and baldness; they’re just one more way of helping people, along with bednets, condoms, and water purification. Donors, how do you feel? Disgusted? Disillusioned? Ready to swear off charity for good? Or interested in learning more?

Thanks to Tim of Philanthropy Action for discussing this issue with me and pointing me to two of the papers above (Dichter; Banerjee/Duflo).

Most of the organizations we’re covering in Africa don’t just do one thing, they do many. I want to get a picture of what the organization as a whole is trying to accomplish (my benchmark is to understand 80% of programs) and the evidence that supports the effectiveness of those programs. I can’t think of any other way to evaluate the efficacy of an organization. It sounds like Holden is worried that asking for 80% is going to be too hard on the charities we’re evaluating. Too hard to explain 80% of what you do? How could that be? If you can’t explain 80% of what you do relatively easily, then there’s just no way that your organization is running effectively. The organizations we fund have to be able to do that.

Most of the organizations we’re covering in Africa don’t just do one thing, they do many. I want to get a picture of what the organization as a whole is trying to accomplish (my benchmark is to understand 80% of programs) and the evidence that supports the effectiveness of those programs. I can’t think of any other way to evaluate the efficacy of an organization. It sounds like Holden is worried that asking for 80% is going to be too hard on the charities we’re evaluating. Too hard to explain 80% of what you do? How could that be? If you can’t explain 80% of what you do relatively easily, then there’s just no way that your organization is running effectively. The organizations we fund have to be able to do that. When a charity does a million things in a million places, it’s futile to try to understand all of it, or even 80%. Speaking very practically, we’ll be taxing the heck out of their development officers, asking for so much information – to say nothing of what we’ll be doing to ourselves. And who cares what all their programs are, anyway? We all know that funders have a tendency to impose their priorities on others. So an org is doing an AIDS program in Kenya because some foundation made them back when AIDS was hip. What does that tell us about the organization’s approach, effectiveness, and more importantly, what they’re going to do with future funds?

When a charity does a million things in a million places, it’s futile to try to understand all of it, or even 80%. Speaking very practically, we’ll be taxing the heck out of their development officers, asking for so much information – to say nothing of what we’ll be doing to ourselves. And who cares what all their programs are, anyway? We all know that funders have a tendency to impose their priorities on others. So an org is doing an AIDS program in Kenya because some foundation made them back when AIDS was hip. What does that tell us about the organization’s approach, effectiveness, and more importantly, what they’re going to do with future funds? Elie and I have been arguing pretty heatedly, and we decided to put our argument online so you all can weigh in if you’d like. The topic is a bit dry, but absolutely essential, and a question that anyone interested in donating can answer. Here’s the question:

Elie and I have been arguing pretty heatedly, and we decided to put our argument online so you all can weigh in if you’d like. The topic is a bit dry, but absolutely essential, and a question that anyone interested in donating can answer. Here’s the question: Holden and I have been reviewing applications for

Holden and I have been reviewing applications for