The next few weeks will be hectic for me and GiveWell. Today, I don’t have time for a post, but I promise you one by midnight (EST) tomorrow.

The GiveWell Blog

What’s in it for me

Today is my first day of working full-time for the Clear Fund. (Technically, since payroll doesn’t start until June, it’s my first day of unemployment.)

Today is my first day of working full-time for the Clear Fund. (Technically, since payroll doesn’t start until June, it’s my first day of unemployment.)

It’s easy to talk about ditching money for meaning, not so easy to do it. And there’s a lot more I’ve walked away from than money. The job situation I’ve left is one that anyone would be lucky to have. I was well treated and well paid. I was surrounded by intelligent and capable people whom I respect. I largely set my own career path. I was challenged, but at the same time I basically had no worries of any kind.

And, I don’t think that what I was doing was without value to society. Hedge funds help move capital to where it will be most productive. Like any other business, they create wealth that can be approximated by looking at their net profits. And any of that wealth that ends up in my pocket can be donated to the charity of my choice.

But I think that I will be way more valuable to the world working for the Clear Fund. My exact analysis of this is a little tangential, so I’ll spill it out another time (or in a comment if someone asks). Briefly, I think that the “pipes” translating wealth into a better world are broken, and that working on those pipes is a more valuable use of my time and talents than generating more wealth to funnel into them.

And that’s what drives my decision. I think being valuable to the world is an incredible desirable thing, in itself. It’s not the only thing I want, but it’s really, really desirable. (I don’t understand people whose goal is to earn so much money that they can be useless for the rest of their lives. Is watching TV all day so awesome that it makes up for having no value? Have I been watching the wrong shows or something?) The more valuable my work is, the more passionate I’ll be about it, the more I’ll enjoy it, the better I’ll do it, and the more my life will be worth living.

This isn’t about leaving a job because it’s boring or bad or makes me feel empty (none of those things applies). This is about leaving a job I like quite a bit for a mission that I’m passionately in love with. Nobody would argue with me about this if we were talking about women instead of jobs … well, my job takes up more of my waking hours than any woman ever will, and having an equally high standard seems appropriate.

Think about how weird it would be if a million dollars in cash were sitting on the sidewalk and everyone was ignoring it. That’s how I feel about the fact that no one else wants to start the world’s first transparent grantmaker.

A few people are incredulous that I’d be so crazy as to voluntarily take a large cut in pay and general security. It’s certainly true we might fail in our mission, and if that happens this will have been a bad move. But if we succeed, people will look back at my decision and be incredulous about something else: that such a tremendous opportunity to be valuable to the world was just sitting there, ready for the taking.

Here goes.

The veil of secrecy is lifted. Ladies, the race is on

As of right now, I no longer have any relationship with any hedge fund or other corporation besides the Clear Fund. That means I no longer have to fear that total idiots will associate the Clear Fund with any other entity. And that means … I can cast off my anonymity, lifting the veil of shadows that has cloaked me since December. While I’m at it, I’ll blow Elie’s and MichiganBob’s cover too. So read on if you dare, and see how deep the rabbit hole goes.

(Warning: this will not actually be the least bit interesting. Turns out, we’re just dudes.)

Secretive, cowardly pseudonym: Holden

Real name: Holden Karnofsky

Grew up in: Chicago ‘burbs

Education: bachelor’s, Harvard

Recent employment: 3 years at a hedge fund

Now lives in: NYC

If he could be any animal, he would be: a guy

Sexy: Yes

Single: Yes

Secretive, cowardly pseudonym: Elie

Real name: Elie Hassenfeld

Grew up in: Boston ‘burbs

Education: bachelor’s, Columbia

Recent employment: 3 years at a hedge fund (still employed)

Now lives in: NYC

If he could be any animal, he would be: a hammerhead shark

Sexy: No

Single: No

Secretive, cowardly pseudonym: MichiganBob

Real name: Bob Elliott

Grew up in: Detroit ‘burbs

Education: bachelor’s, Harvard

Recent employment: 2 years at a hedge fund (still employed)

Now lives in: CT

If he could be any animal, he would be: an altruistic mosquito, refusing to transmit malaria

Sexy: Yes

Single: No

The three of us are men – but some of our best friends are women, we swear.

So there you go, we’re real people now. To all you anonymity haters, I hope you’ve learned what you wanted to know, and that you now have a much better ability to engage critically with what we write. To those of you who are capable of analyzing the content of sentences on your own, this post may have been a waste of your time, but at least I warned you.

(Note: this blog post was made without input from Elie or MichiganBob.)

Do any charities know what they’re doing?

Do any charities know what they’re doing?

We think so. In fact, we’re banking on it. GiveWell’s mission is to help steer capital and foster dialogue, and that’s it. We plan to give grants the same way we’ve given our personal donations: look for charities that already have proven, effective, scalable ways of helping people – charities that already know what they’re doing – and give them money. No consulting, no expertise, no program development, and no restrictions. Money.

We think so. In fact, we’re banking on it. GiveWell’s mission is to help steer capital and foster dialogue, and that’s it. We plan to give grants the same way we’ve given our personal donations: look for charities that already have proven, effective, scalable ways of helping people – charities that already know what they’re doing – and give them money. No consulting, no expertise, no program development, and no restrictions. Money.

For-profit sector readers are probably bored right now and wondering whether I’m going to say anything, but I bet the same isn’t true of nonprofit sector readers. From everything I’ve seen, our model of grantmaking is the exception, not the rule. Foundations don’t fund charities, they fund projects; they design programs and agendas, then look for organizations that fit into them; they design project-specific budgets, then make sure each of “their” dollars goes where it’s supposed to.

Part of it may be that foundations consider themselves experts in their fields, and they think they know more than the charities they fund. And they might be right … but that isn’t how we think of ourselves. We have a lot of options, so we demand a ton of information from charities, and we demand that they engage our questions and suggestions intelligently – but in the end, they know way more about their work than we do, and they should be the ones to decide how they do it. The donor’s role is to fund it.

Part of it may be that foundations consider themselves experts in their fields, and they think they know more than the charities they fund. And they might be right … but that isn’t how we think of ourselves. We have a lot of options, so we demand a ton of information from charities, and we demand that they engage our questions and suggestions intelligently – but in the end, they know way more about their work than we do, and they should be the ones to decide how they do it. The donor’s role is to fund it.

It seems clear to me that this is would be a disastrous strategy if we didn’t pick our charities carefully. Hey – that’s exactly how it works today, with the lion’s share of charitable capital coming from people who have no access to good information (though at least they can get irrelevant financial data and nonsensical metrics).

But imagine if we actually put in the due diligence, and find the charities that already have smart, experienced, passionate people with proven, effective, scalable methods for helping people. Imagine if we find the organizations that have it all except money. At that point, it’s moot how much of our dollar is going to “overhead,” or anything else – sometimes overhead is necessary and sometimes it isn’t, and good people will make those decisions better than we can. At that point, it’s unnecessary for us to “keep the charities in line,” because they’ll keep themselves in line or lose next time around. Accountability, transparency, and competition are harsher taskmasters than any contract can be.

But imagine if we actually put in the due diligence, and find the charities that already have smart, experienced, passionate people with proven, effective, scalable methods for helping people. Imagine if we find the organizations that have it all except money. At that point, it’s moot how much of our dollar is going to “overhead,” or anything else – sometimes overhead is necessary and sometimes it isn’t, and good people will make those decisions better than we can. At that point, it’s unnecessary for us to “keep the charities in line,” because they’ll keep themselves in line or lose next time around. Accountability, transparency, and competition are harsher taskmasters than any contract can be.

When we find what we’re looking for, we’re looking at an alley-oop … all we have to do is throw them the ball. That’s going to be easier and more effective than doing the driving ourselves.

What is success?

Disclaimer: GiveWell failed to be named as one of NetSquared’s featured projects. Therefore, if you are incapable of making your own judgments about what you read (based on content rather than author), you should assume that the blog post that follows is just me being “bitter,” and you should load a reputable news site immediately before you read something dangerous. Those who are comfortable differentiating reasonable from unreasonable, feel free to proceed.

As of last Wednesday at ~8pm est,

- NetSquared had recently closed its online balloting to choose the featured projects for its upcoming conference.

- Many concerns had been expressed over the completely open online ballot.

- No one knew yet who had voted, how many people had voted, or how many votes were based in any way on content of proposals (as opposed to emails from friends).

- No one knew which projects had won yet.

- No one knew anything about the projects themselves, beyond what was written up briefly in their proposals.

- There had been close to zero substantive discussion of the proposals.

And here was what people were saying about it:

- Phil proclaimed the vote a “watershed event for democracy.”

- I eagerly anticipated other blogs’ making fun of him for jumping the gun. Phil is a good and thought-provoking writer who is not always what we would call “reserved” in tone.

- Lucy agreed with Phil.

- So did the normally reserved Sean.

- In the wake of criticism, Sean insisted that “NetSquared is already a success” – not because of its voting process (the original thing that had set off Phil), but because the projects that are going to be featured are “great.” (Keep in mind that the sum total of our knowledge on these projects still consists of ~1000 words submitted by their leaders.)

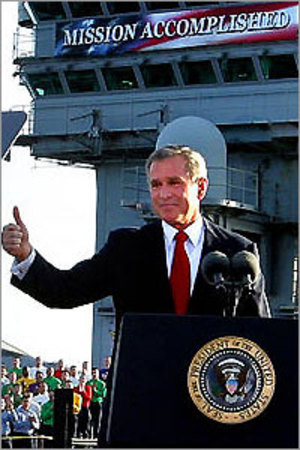

To be clear, I think NetSquared is an exciting idea. But where I come from, people celebrate a new client the day the client signs, not the day they decide to call the client and see if they’re interested. “Great research projects” refers to ideas that have been studied and stress-tested to death and produced returns, not to the ideas we had in this morning’s meeting. So as I’ve made clear, I’ve been pretty surprised by the extent to which people have called paragraphs on a screen “great projects,” and pointed to a “success” and “watershed event” where I saw an online poll that hadn’t even been tallied yet.

To be clear, I think NetSquared is an exciting idea. But where I come from, people celebrate a new client the day the client signs, not the day they decide to call the client and see if they’re interested. “Great research projects” refers to ideas that have been studied and stress-tested to death and produced returns, not to the ideas we had in this morning’s meeting. So as I’ve made clear, I’ve been pretty surprised by the extent to which people have called paragraphs on a screen “great projects,” and pointed to a “success” and “watershed event” where I saw an online poll that hadn’t even been tallied yet.

And while I can only speak to what I’ve seen, this doesn’t strike me as an isolated incident. The charities I’ve examined constantly use the word “success” to refer to mosquito nets purchased or children enrolled in an after-school program, or even in many cases simply dollars spent or plans made. Much of the literature I’ve read on grantmaking tells stories of “great grantmaking,” stories that end with the funds disbursed. Call me crazy, but for a humanitarian charity I associate “success” with “lives changed.”

Sure, that’s hard to measure. Yes, many of the things we celebrate in the for-profit sector are more concrete. But this post isn’t about the process of evaluation (I’ve written plenty about that, and will write plenty more); it’s about the mentality. When you’re used to seeing the results of your actions, you’re used to the world’s working much less smoothly than your imagination does. You assume a huge chasm between a great idea and a great result. You put the bar for “success” a lot higher, and that pushes you to get a lot better. I wish I saw more of this mentality from the sector whose job it is to bring about the world’s most important (and often most difficult) changes.

Spending the better half

Our fundraising efforts have started, and dang, do I hate asking for money. For three years, I’ve had way more income than I can spend, and I’ve rarely had to ask anyone for anything. That’s a nice position to be in. This – especially for an abrasive guy like me – is tough.

Our fundraising efforts have started, and dang, do I hate asking for money. For three years, I’ve had way more income than I can spend, and I’ve rarely had to ask anyone for anything. That’s a nice position to be in. This – especially for an abrasive guy like me – is tough.

A common saying in the world of charity is: “Spend the first half of your life making money, and the second half giving it away.” As it’s become clear that GiveWell needs to be a full-time project, this saying has popped into my head a lot, and never more than now. Why not put off helping others until I’ve given myself more help than I can possibly use? Why not stay in finance, which I like fine, until I’ve accumulated such a massive fortune that I can finance GiveWell all by myself?

In exchange for letting the world wait a decade or two, I’d gain the freedom to do this project my way and only my way. I wouldn’t need a business plan and an elevator pitch and the incredible amount of work that goes between thinking and communicating. I wouldn’t need to fundraise; I wouldn’t need friends and allies; I wouldn’t need favors; I wouldn’t need anyone’s approval or permission.

And so, I’d do a much worse job.

Not even my incredible brain can look at things from as many angles as a roomful of different people; not even my awe-inspiring self-discipline will make me consider those angles as sincerely and thoughtfully as I do when I have to. If I can’t make GiveWell speak to people enough for them to put their money behind it, it will go nowhere. And if I do make it speak to them but I can’t follow through, I’ll be humiliated and devastated in a way that wasting spare cash of my own could never make me. These are the pressures that startups face, and the world is a better place because of it.

That’s why you should be concerned that philanthropy is currently seen as something to do with the “second half” of your life. “Second half” here isn’t just chronological – it’s referring to the half that specifically isn’t where the philanthropist made their name. The second half is the half that lacks risk, accountability, and the people who keep one honest (a set of factors collectively known as the “eye of the tiger”). All the great foundations today are following the orders of people who’ve made their fortune doing something else, and who no longer have to consider any criticism they don’t care for. I have to believe that matters, no matter how good their intentions.

That’s why you should be concerned that philanthropy is currently seen as something to do with the “second half” of your life. “Second half” here isn’t just chronological – it’s referring to the half that specifically isn’t where the philanthropist made their name. The second half is the half that lacks risk, accountability, and the people who keep one honest (a set of factors collectively known as the “eye of the tiger”). All the great foundations today are following the orders of people who’ve made their fortune doing something else, and who no longer have to consider any criticism they don’t care for. I have to believe that matters, no matter how good their intentions.

The first half of life is where people do great things or fall by the wayside. I want to spend that half “giving it away,” and if you’re a donor or just a supporter, you should be glad that’s the half you’re getting.