We’ve continued to look into scientific research funding for the purposes of the Open Philanthropy Project. This hasn’t been a high priority for the last year, and our investigation remains preliminary, but I plan to write several posts about what we’ve found so far. Our early focus has been on biomedical research specifically.

Most useful new technologies are the product of many different lines of research, which progress in different ways and on different time frames. I think that when most people think about scientific research, they tend to instinctively picture only a subset of it. For example, people hoping for better cancer treatment tend instinctively to think about “studying cancer” as opposed to “studying general behavior of cells” or “studying microscopy techniques,” even though all three can be essential for making progress on cancer treatment. Picturing only a particular kind of research can affect the way people choose what science to support.

I’m planning to write a fair amount about what I see as promising approaches to biomedical sciences philanthropy. Much of what I’m interested in will be hard to explain without some basic background and vocabulary around different types of research, and I’ve been unable to find an existing guide that provides this background. (Indeed, many of what I consider “overlooked opportunities to do good” may be overlooked because of donors’ tendencies to focus on the easiest-to-understand types of science.)

This post will:

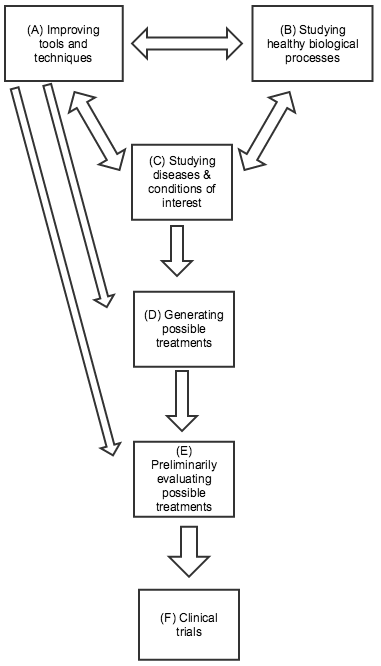

- Lay out a basic guide to the roles of different types of biomedical research: improving tools and techniques, studying healthy biological processes, studying diseases and conditions of interest, generating possible treatments, preliminarily evaluating possible treatments, and clinical trials.

- Use the example of the cancer drug Herceptin to compare the roles of these different sorts of research more concretely.

- Go through what I see as some common misconceptions that stem from overfocusing on a particular kind of research, rather than on the complementary roles of many kinds of research.

Below are some distinctions I’ve found it helpful to draw between different kinds of research. This picture is highly simplified: many types of research don’t fit neatly into one category, and the relationships between the different categories can be complex: any type of research can influence any other kind. In the diagram to the right (click to expand), I’ve highlighted the directions of influence I believe are generally most salient.

(A) Improving tools and techniques. Biomedical researchers rely on a variety of tools and techniques that were largely developed for the general purpose of measuring and understanding biological processes, rather than with any particular treatment or disease/condition in mind. Well-known examples include microscopes and DNA sequencing, both of which have been essential for developing more specific knowledge about particular diseases and conditions. More recent examples include CRISPR-related gene editing techniques, RNA interference, and using embryonic stem cells to genetically modify mice. All three of these provide ways of experimenting with changes in the genetic code and seeing what results. The former two may have direct applications for treatment approaches in addition to their value in research; the latter two were both relatively recently honored with Nobel Prizes. Improvements in tools and techniques can be a key factor in improving most kinds of research on this list. Sometimes improvements in tools and techniques (e.g., faster/cheaper DNA sequencing; more precise microscopes) can be as important as the development of new ones.

(B) Studying healthy biological processes. Basic knowledge about how cells function, how the immune system works, the nature of DNA, etc. has been essential to much progress in biomedical research. Many of the recent Nobel Prizes in Physiology or Medicine were for work in this category, some of which led directly to the development of new tools and techniques (as in the case of CRISPR-based gene editing, which is drawn from insights about bacterial immune systems).

(C) Studying diseases and conditions of interest. Much research focuses on understanding exactly what causes a particular disease and condition, as specifically and mechanistically as possible. Determining that a disease is caused by bacteria, a virus, or by a particular overactive gene or protein can have major implications for how to treat it; for example, the cancer drug Gleevec was developed by looking for a drug that would bind to a particular protein, which researchers had identified as key to a particular cancer. Note that (C) and (B) can often be tightly intertwined, as studying differences between healthy and diseased organisms can tell us a great deal both about the disease of interest and about the general ways in which healthy organisms function. However, (B) may have more trouble attracting support from non-scientists, since the applications can be less predictable and clear.

(D) Generating possible treatments. No matter how much we know about the causes of a particular disease/condition, this doesn’t guarantee that we’ll be able to find an effective treatment. Sometimes (as with Herceptin – more below) treatments will suggest themselves based on prior knowledge; other times the process comes down largely to trial and error. For example, malaria researchers know a fair amount about the parasite that causes malaria, but have only identified a limited number of chemicals that can kill it; because of the ongoing threat of drug resistance developing, they continue to go through many thousands of chemicals per year in a trial-and-error process, checking whether each shows potential for killing the relevant parasite. (Source)

(E) Preliminarily evaluating possible treatments (sometimes called “preclinical” work). Possible treatments are often first tested “in vitro” – in a simplified environment, where researchers can isolate how they work. (For example, seeing whether a chemical can kill isolated parasites in a dish.) But ultimately, a treatment’s value depends on how it interacts with the complex biology of the human body, and whether its benefits outweigh its side effects. Since clinical trials (next paragraph) are extremely expensive and time-consuming, it can be valuable to first test and refine possible treatments in other ways. This can include animal testing, as well as other methods for predicting a treatment’s performance.

(F) Clinical trials. Before a treatment comes to market, it usually goes through clinical trials: studies (often highly rigorous experiments) in which the treatment is given to humans and the results are assessed. Clinical trials typically involve four different phases: early phases focused on safety and preliminary information, and later phases with larger trials focused on definitively understanding the drug’s effects. Many people instinctively picture clinical trials when they think about biomedical research, and clinical trials account for a great deal of research spending (one estimate, which I haven’t vetted, is that clinical trials cost tens of billions of dollars a year, over half of industry R&D spending). However, the number of clinical trials going on generally is – or should be – a function of the promising leads that are generated by other types of research, and the most important leverage points for improving treatment are often within these other types of research.

(A) – (C) are generally associated with academia, while (D) – (F) are generally associated with industry. There are a variety of more detailed guides to (D) – (F), often referred to as the “drug discovery process” (example).

Here I list, in chronological order, some of the developments which seem to have been crucial for developing Herceptin. My knowledge of this topic is quite limited, and I don’t mean this as an exhaustive list. I also wish to emphasize that many of the items on this list were the result of general inquiries into biology and cancer – they weren’t necessarily aimed at developing something like Herceptin, but they ended up being crucial to it. Throughout this summary, I note which of the above types of research were particularly relevant, using the same letters in parentheses that I used above.

- In the 1950s, there was a great deal of research focused on understanding the genetic code (B). For purposes of this post, it’s sufficient to know that a gene serves the function of a set of instructions for building a protein, a kind of molecule that can come in many different forms serving a variety of biological functions. The research that led to understanding the genetic code was itself helped along by multiple new tools and techniques (A) such as Linus Pauling’s techniques for modeling possible three-dimensional structures (more).

- In the 1970s, studies on chicken viruses that were associated with cancer led to establishing the idea of an oncogene: a particular gene (often resulting from a mutation) that, when it occurs, causes cancer. (C)

- In 1983, several scientists established a link between oncogenes and a particular sort of protein called epidermal growth factor receptors (EGFRs), which give cells instructions to grow and proliferate. In particular, they determined that a particular EGFR was identical to the protein associated with a known chicken oncogene. This work was a mix of (B) and (C), as it grew partly out of a general interest in the role played by EGFRs. It also required being able to establish which gene coded for a particular protein, using techniques that were likely established in the 1970s or later (A).

- In 1986, an academic scientist collaborated with Genentech to analyze the genes present in a series of cancerous tumors, and cross-reference them with a list of possible cancer-associated EGFRs (C). One match involved a particular gene called HER2/neu; tumors with this gene (in a mutated form) showed excessive production of the associated protein, which suggested that (a) the mutated HER2/neu gene was overproducing HER2/neu proteins, causing excessive cell proliferation and thus cancer; (b) this particular sort of cancer might be mitigated if one could destroy or disable HER2/neu proteins. This work likely benefited from advances in being able to “read” a genetic code more cheaply and quickly.

- The next step was to find a drug that could destroy or disable the HER2/neu proteins (D). This was done using a relatively recent technique (A), developed in the 1970s, that relied on a strong understanding of the immune system (B) and of another sort of cancer that altered the immune system in a particular way (C). Specifically, researchers were able to mass-produce antibodies designed to recognize and attach to the EGFR in question, thus signaling the immune system to destroy them.

- At that time, monoclonal antibodies (mass-produced antibodies as described above) were seen as highly risky drug candidates, since they were produced from other animals and likely to be rejected by human immune systems. However, in the midst of the research described above, a new technique (A) was created for getting the body to accept these antibodies, greatly improving the prospects for getting a drug.

- Researchers then took advantage of a relatively recent technique (A) for inserting human tumors into modified mice, which allowed them to test the drug and produce compelling preliminary evidence (E) that the drug might be highly effective.

- At this point – 1988 – there was a potential drug and some supportive evidence behind it, but its ultimate effect on cancer in humans was unknown. It would be another ten years before the drug went through all relevant clinical trials (F) and received FDA approval, under the name Herceptin. Her-2: The Making of Herceptin gives a great deal of detail on the challenges of this period.

As detailed above, many essential insights necessary for Herceptin’s development came out very long before the idea of Herceptin had been established. My impression is that most major biomedical breakthroughs of the last few decades have a similar degree of reliance on a large number of previous insights, many of them fundamentally concerning tools and techniques (A) or the functioning of healthy organisms (B) rather than just disease-specific discoveries.

- “Publicly funded research is unnecessary; the best research is done in the for-profit sector.” My impression is that most industry research falls into categories (D)-(F). (A)-(C), by contrast, tend to be a poor fit for industry research, because they are so far removed from treatments both in terms of time and risk. Because it is so hard to say what the eventual use is of a new tool/technique or insight into healthy organisms, it is likely more efficient for researchers to put insights into the public domain rather than trying to monetize them directly.

- “Drug companies don’t do valuable research – they just monetize what academia provides them for free.” This is the flipside of the above misconception, and I think it overfocuses on (A)-(C) without recognizing the challenges and costs of (D)-(F). Given the very high expenses of research in categories (D)-(F), and the current norms and funding mechanisms of academia, (D)-(F) are not a good fit for academia.

- “The best giving opportunities will be for diseases that aren’t profitable for drug companies to work on.” This might be true for research in categories (D)-(F), but one should also consider research in categories (A)-(C); this research is generally based on a different set of incentives from those of drug companies, and so I’d expect the best giving opportunities to follow a different pattern.

- “Much more is spent on disease X than disease Y; therefore disease Y is underfunded.” I think this kind of statement often overweights the importance of (F), the most expensive but not necessarily most crucial category of research. If more is spent on disease X than on disease Y, this may be simply because there are more promising clinical trial candidates for disease X than disease Y. Generally, I am wary of “total spending” figures that include clinical trials; I don’t think such figures necessarily tell us much about society’s priorities.

- “Academia is too focused on knowledge for its own sake; we need to get it to think more about practical solutions and treatments.” I believe this attitude undervalues (A)-(B) and understates how important general insights and tools can be.

- “We should focus on funding research with a clear hypothesis, preliminary support for the hypothesis, and a clear plan for further testing the hypothesis.” I’ve heard multiple complaints that much of the NIH takes this attitude in allocating funding. Research in category (A) is often not hypothesis-driven at all, yet can be very useful. More on this in a future post.

- “The key obstacles to biomedical progress are related to reproducibility and reliability of studies.” I think that reproducibility is important, and potentially relevant to most types of research, but it is most core to clinical trials (F). Studies on humans are generally expensive and long-running, and so they may affect policy and practice for decades without ever being replicated. By contrast, for many other kinds of research, there is some cheap effective “replication” – or re-testing of the basic claims – via researchers trying to build on insights in their own lab work, so a non-reproducible study might in many cases mean a relatively modest waste of resources. I’ve heard varying opinions on how much waste is created by reproducibility-related issues in early-stage research, and think it is possible that this issue is a major one, but it is far from clear that it is the key issue.