In addition to evaluations of other charities, GiveWell publishes substantial evaluation of itself, from the quality of its research to its impact on donations. We publish quarterly updates regarding two key metrics: (a) donations to top charities and (b) web traffic.

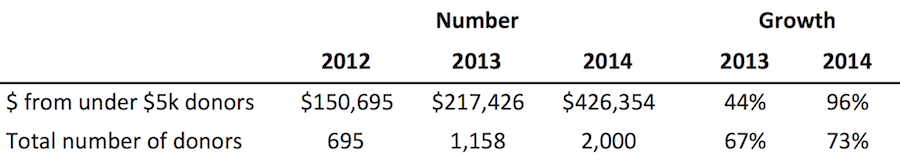

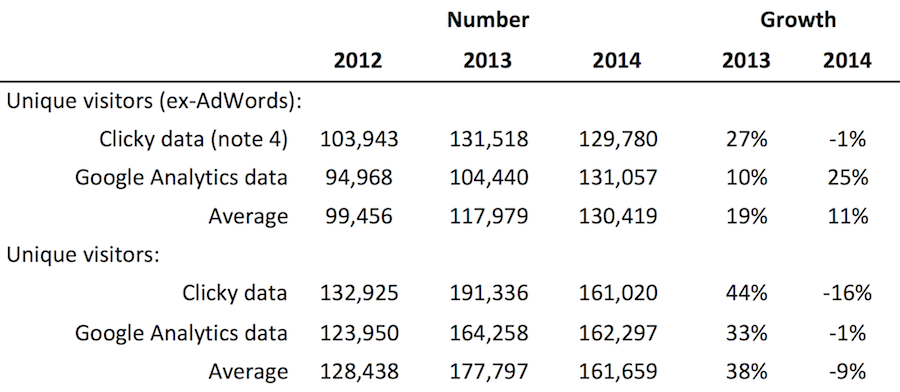

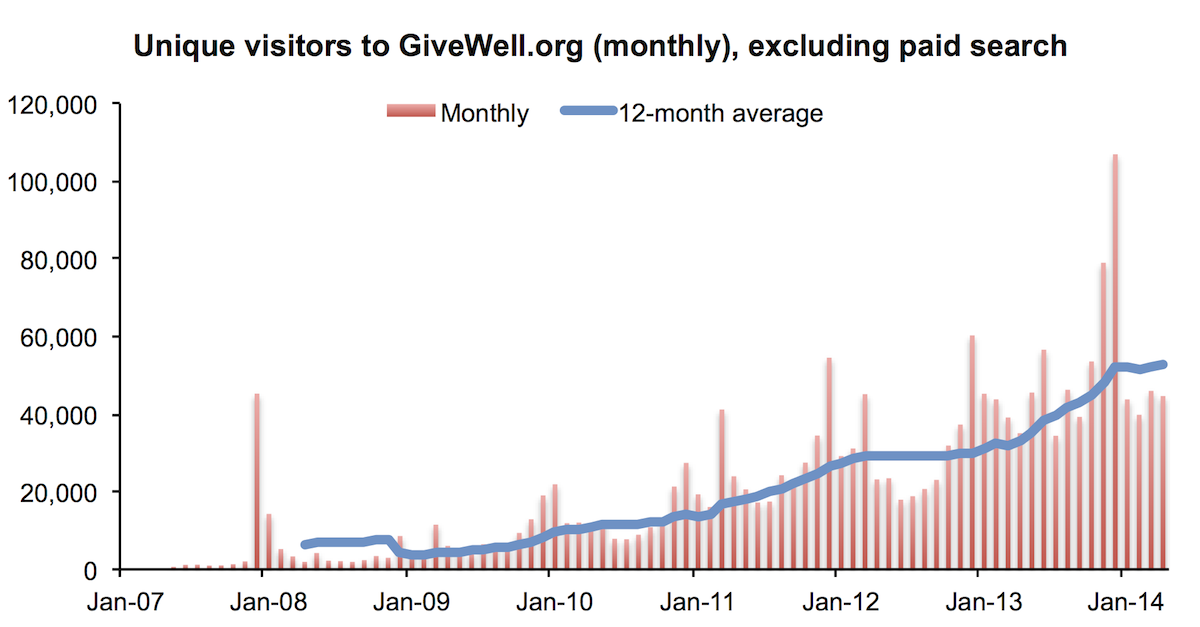

The table and chart below present basic information about our growth in money moved and web traffic in the first quarter of 2014 (note 1).

Growth in money moved, as measured by donations from donors giving less than $5,000 per year, was strong in the first quarter of 2014 (money moved was 96% higher than in the first quarter of 2013), and was substantially stronger than growth in the first quarter of 2013. The total amount of money we move is driven by a relatively small number of large donors. These donors tend to give in December, and we don’t think we have accurate ways of predicting future large gifts (note 2). We therefore show growth among small donors, the portion of our money moved about which we think we have meaningful information at this point in the year.

Growth in number of donors was also strong, and similar to growth in this metric in the first quarter of 2013.

In the past, we have relied on data from the web analytics company Clicky for our metrics updates. We also track web traffic through Google Analytics, and between January 2012 and February 2014, Google Analytics consistently tracked lower overall traffic than Clicky. We do not know what the cause of the discrepancy between the two sources is, and do not have a view on which data source is more likely to be correct. For that reason, we present data from both sources here. Full data set available at this spreadsheet. (Note on how we count unique visitors.)

Traffic from AdWords decreased in the first quarter because in early 2014 we removed ads on searches that we determined were not driving high quality traffic to our site (i.e. searches with very high bounce rates and very low pages per visit).

Data in the chart below is an average of Clicky and Google Analytics data, except for those months for which we only have data (or reliable data) from one source (see full data spreadsheet for details).

Note 1: Since our 2012 annual metrics report we have shifted to a reporting year that starts on February 1, rather than January 1, in order to better capture year-on-year growth in the peak giving months of December and January. Therefore metrics for the “first quarter” reported here are for February through April.

Note 2: In total, GiveWell donors have directed $1.45 million to our top charities this year, compared with $0.70 million at this point in 2013. For the reason described above, we don’t find this number to be particularly meaningful at this time of year.

Note 3: We count unique visitors over a period as the sum of monthly unique visitors. In other words, if the same person visits the site multiple times in a calendar month, they are counted once. If they visit in multiple months, they are counted once per month.

Note 4: Google Analytics provides ‘unique visitors by traffic source’ while Clicky provides only ‘visitors by traffic source.’ For that reason, we primarily use Google Analytics data in the calculations of ‘unique visitors ex-AdWords’ for both the Clicky and Google Analytics rows of the table. See the full data spreadsheet, sheets Data and Summary, for details.