This is the third post (of six) we’re planning to make focused on our self-evaluation and future plans.

This post answers a set of critical questions about the state of GiveWell as a donor resource. The questions are the same as last year’s.

Does GiveWell provide quality research that highlights truly outstanding charities in the areas it has covered?

Where we stood as of Feb 2011

- Internally, we were satisfied with the quality of our research as compared to other options for donors.

- We planned to complete a new round of research focused on international aid to find additional top charities.

- We planned to complete regular updates for VillageReach, our top-rated charity in 2009 and 2010 and the first charity to which we moved significant (now more than $2 million) funds.

- We felt a need for more substantial external checks on our research. In the previous year, we had several reviews completed, but we believed additional reviews were necessary.

- Our research process was constrained because of our inability to offer project-based funding.

Progress since Feb 2011

In Feb 2011, we wrote that we hoped for

More intensive examination of our top-rated charities (the ones that attract the lion’s share of our “money moved”), including in-person site visits, continual updates on room for more funding, and conversations with major funders who have agreed – or declined – to fund them.

In 2011, we did all of these things.

- The level of vetting to which we subject our top charities has increased significantly.

- We visited all three leading contenders for our highest ratings in October before giving them our top rating. We intend to continue this and visit charities before we give them our top ratings.

- We conducted extensive reviews of the cost-effectiveness and evidence of effectiveness for the programs run by our top charities, which went significantly beyond our independent assessments of research in previous years. (See our writeups on ITNs and deworming.)

- We have completed regular updates on VillageReach’s progress.

- We have received several additional external reviews of our research, but our attempts to significantly expand this process were not successful. We intend to revisit this in 2012.

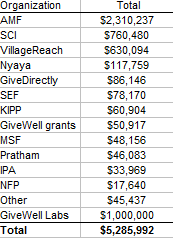

- In addition, we launched GiveWell Labs, a new arm of our research process that will be open to any giving opportunity, no matter what form and what sector, in the hopes of improving our ability to find great giving opportunities.

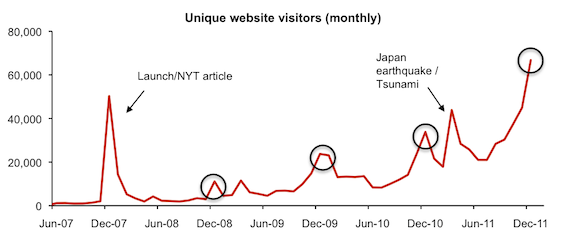

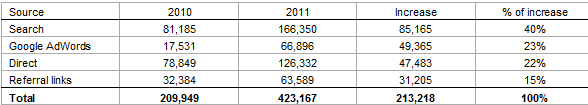

As our influence has increased, our ability to get access to relevant people such as charity representatives, scholars, and major funders has improved. (For example, see our investigation of targeted vs. universal coverage for insecticide-treated nets.) This, along with growth in our team, have improved our ability to do in-depth research efficiently.

Where we stand

We feel that our current research is high-quality and up-to-date. We are not satisfied with our total “room for money moved.” We estimate that our top charities have roughly $15-20 million in available room for more funding, which is substantially more than we have directed to them, but not necessarily “enough” if our influence were to continue growing rapidly.

We also feel there are multiple areas that could offer outstanding opportunities that we have not yet researched as thoroughly as we could (particularly in the areas of nutrition, vaccinations, neglected tropical disease control, tuberculosis control, and research and development).

We also continue to see room for improvement in our coverage of top charities.

- We’d like to continue to increase our qualitative checks on top charities, particularly conversations with those who have funded them or chosen not to.

- We remain unsatisfied with the degree to which our research is “vetted.” It still seems to us that we could make a substantial mistake or error in judgment, with too high a probability that it would remain unnoticed. We feel that this is much less true today than ever before, because (a) our staff is larger and we subject important pages to multiple checks from different people; (b) our research draws more attention, including from donors who are giving large amounts and vetting our work fairly closely. We feel that the degree to which our work is “vetted” will grow as our overall influence and prominence grows, though putting more effort into formal external reviews help as well.

What we can do to improve

- Revisit the goal of having our work subjected to formal, consistent, credible external review.

- Continue to look for more outstanding giving opportunities for individual donors, particularly (a) in the areas we have identified as most promising (b) through GiveWell Labs.