I wonder how much of the difference between our approach to charity and others’ approach comes from this very simple fact:

We think that improving people’s lives is really hard.

It might be easy to brighten someone’s day, even their week. But to get someone from poverty and misery to self-sufficiency and a world of opportunity … you have to change not just their resources, but their skills, often their attitude, and always their behavior. You can try to do this early in life or late; either way, it’s an uphill battle.

As we’ve been over and over, that’s why we think “money spent” is a poor proxy for “good accomplished,” and tend not to get as excited as others over dollars raised or dollars spent. But as we get deeper into reading apps, I’m finding there’s more and more to this rift.

I’m very skeptical of any program that claims great effects with relatively low amounts of intervention, whether it’s a one-time class on condom use or a once-a-week tutoring session. I think about how easy it is for the people I know to sit through some class, walk out full of ideas, and forget them a week later, and I think – if you’re doing anything meaningful for people with this little investment, you must be some sort of sorceror.

I’m very skeptical of any program that claims great effects with relatively low amounts of intervention, whether it’s a one-time class on condom use or a once-a-week tutoring session. I think about how easy it is for the people I know to sit through some class, walk out full of ideas, and forget them a week later, and I think – if you’re doing anything meaningful for people with this little investment, you must be some sort of sorceror.

I trust survey data about as far as I can throw it (note: data cannot be thrown). Katya’s post today gives a sniff of the argument that “people are notoriously bad predictors of their behavior”; there’s actually an enormous amount of literature out there ramming home this point (if you really want to see it, let me know). We’ve seen a lot of survey data along the lines of “97% of participants felt the program improved their ability to ___,” which would be great if wishes were horses and horses were great.

I tend to feel the same way about anecdotes and personal experiences. They can be useful to get a picture of a program, but as evidence that it works? People are easy to change in the moment and incredibly hard to change in the long run. How can you possibly tell from watching a group of children for a year that they’re headed for better lives?

And in the end, though I keep reminding myself that evidence of effectiveness can come in all different forms, I can’t keep down that longing for randomized studies, or at least studies that employ some sort of comparison group. These are very rare in the applications we’re receiving: charities tend to look only at their clients. While this clearly saves them a lot of money and hassle, it leaves me wondering whether they’re really helping people … or just picking out the ones who are going to succeed anyway (you’re probably familiar with this question in the context of Ivy League schools). I’m sure this is heresy, but if we started a Placebo Foundation that sought out the “most motivated” poor people as clients, did absolutely nothing for them, and then examined their outcomes, would we find the same “successes” that many charities claim?

And yet every study I’ve read from applicants – even when limited to survey data, even when lacking a comparison group of any kind – concludes that the program in question was a success.

Unless there’s willful deception going on here, this implies to me that the people who work at charities think helping people is really, really easy; that there’s no need to worry about all the questions above; that the flimsiest and most perfunctory of evidence is good enough to walk away from feeling that people in need have been truly helped.

Maybe we’re wrong. Maybe helping people is that simple. If that’s what you think, keep writing those checks to whomever sends you mail, and make sure they aren’t blowing a penny more than they have to on salaries. If you’re concerned as I am, though, I’ve got some tough news from you: aside from GiveWell, I don’t think you have much company.

If a charity doesn’t follow up with its clients, it will never know whether its efforts are very successful, moderately successful, or entirely worthless. It will have no way of figuring out when the plan that made sense in its director’s head is falling short in reality. It could keep doing things that make logical sense, but don’t work at all, for hundreds of years – and never find out. None of that is true of any business.

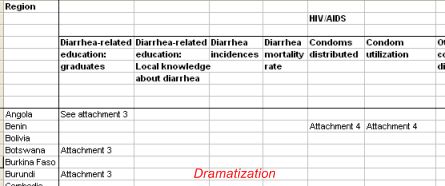

If a charity doesn’t follow up with its clients, it will never know whether its efforts are very successful, moderately successful, or entirely worthless. It will have no way of figuring out when the plan that made sense in its director’s head is falling short in reality. It could keep doing things that make logical sense, but don’t work at all, for hundreds of years – and never find out. None of that is true of any business. We’ve dubbed this app The Matrix, because its key feature is a gigantic matrix of regions and indicators – we want to know what each charity does and doesn’t have data on, in every region it works in. It’s visually gargantuan, but we’re not asking applicants to fill in statistics in the cells. All we’re asking is that they tell us what they do and don’t do – and what they do and don’t measure – in each of their regions.

We’ve dubbed this app The Matrix, because its key feature is a gigantic matrix of regions and indicators – we want to know what each charity does and doesn’t have data on, in every region it works in. It’s visually gargantuan, but we’re not asking applicants to fill in statistics in the cells. All we’re asking is that they tell us what they do and don’t do – and what they do and don’t measure – in each of their regions. I don’t hold small organizations, or simple organizations, to the same standard of measurement and organization. A bicycle doesn’t need a dashboard, because you can tell immediately if something’s wrong; unmetaphorically, if you work in one place, doing one thing, you can be part of the day-to-day activities and understand them intuitively, without ever measuring or documenting a thing. But for the life of me, I can’t understand how it’s possible to have an “intuitive” feel for your work when you’re trying to help thousands of different people, thousands of miles away, living in cultures and regions you didn’t grow up in and will never truly understand. It seems like the only way to have any idea of what’s going on is to collect an enormous quantity of facts and put great care into interpreting and organizing them. Elie and I recognize that we aren’t experienced in these matters … but the idea that an organization would take weeks to put together a summary of what it does and whether it works is just hard for us to swallow.

I don’t hold small organizations, or simple organizations, to the same standard of measurement and organization. A bicycle doesn’t need a dashboard, because you can tell immediately if something’s wrong; unmetaphorically, if you work in one place, doing one thing, you can be part of the day-to-day activities and understand them intuitively, without ever measuring or documenting a thing. But for the life of me, I can’t understand how it’s possible to have an “intuitive” feel for your work when you’re trying to help thousands of different people, thousands of miles away, living in cultures and regions you didn’t grow up in and will never truly understand. It seems like the only way to have any idea of what’s going on is to collect an enormous quantity of facts and put great care into interpreting and organizing them. Elie and I recognize that we aren’t experienced in these matters … but the idea that an organization would take weeks to put together a summary of what it does and whether it works is just hard for us to swallow. When I first heard about microfinance, everywhere I turned was a story like

When I first heard about microfinance, everywhere I turned was a story like

Most of the organizations we’re covering in Africa don’t just do one thing, they do many. I want to get a picture of what the organization as a whole is trying to accomplish (my benchmark is to understand 80% of programs) and the evidence that supports the effectiveness of those programs. I can’t think of any other way to evaluate the efficacy of an organization. It sounds like Holden is worried that asking for 80% is going to be too hard on the charities we’re evaluating. Too hard to explain 80% of what you do? How could that be? If you can’t explain 80% of what you do relatively easily, then there’s just no way that your organization is running effectively. The organizations we fund have to be able to do that.

Most of the organizations we’re covering in Africa don’t just do one thing, they do many. I want to get a picture of what the organization as a whole is trying to accomplish (my benchmark is to understand 80% of programs) and the evidence that supports the effectiveness of those programs. I can’t think of any other way to evaluate the efficacy of an organization. It sounds like Holden is worried that asking for 80% is going to be too hard on the charities we’re evaluating. Too hard to explain 80% of what you do? How could that be? If you can’t explain 80% of what you do relatively easily, then there’s just no way that your organization is running effectively. The organizations we fund have to be able to do that.