I recently spoke with Robin Hanson and he proposed that donors invest their money in order to give more in the future.

One question that came up was whether the world is improving such that opportunities to cost-effectively accomplish good are running out.

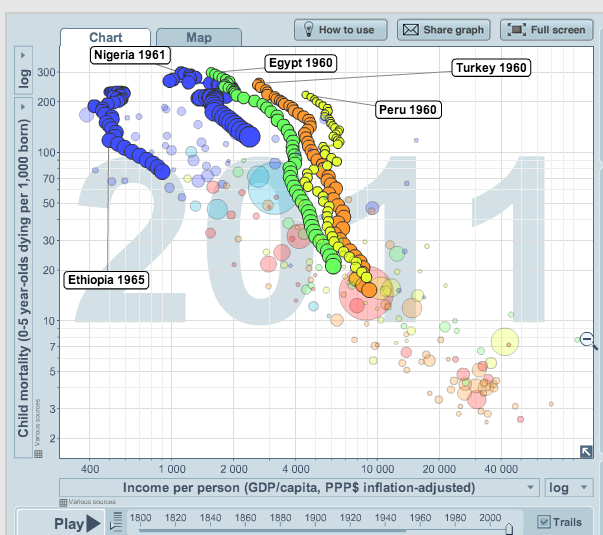

I think there’s a strong argument that this may be the case, at least when it comes to improving the health and opportunities of the world’s poorest. The following charts illustrate that child deaths have been falling dramatically and population growth has been slowing as incomes have risen. (In the charts, the trails show each country’s changes over time, from the first year noted in the bubble with the country’s name until the present day.)

The graphs below come from Gapminder.org. The charts below only show several countries for several indicators, but they’re broadly representative of what has happened. To see more, click through to Gapminder.