We previously wrote about our general principles for assessing evidence, where “evidence” is construed broadly (it may include awards/recognition/reputation, testimony, and broad trends in data as well as formal studies). Here we discuss our approach to a particular kind of evidence, what we call “micro data”: formal studies of the impact of a program on a particular population at a particular time, using quantitative data analysis.

We list several principles that are important to us in deciding how much weight to put on a study’s claims. A future post will discuss the application of these principles to some example studies.

One way to deal with the problem of causal attribution is via randomization. A randomized controlled trial (in this context) is a study in which a set of people is identified as potential program participants, and then randomly divided into one or more “treatment group(s)” (group(s) participating in the program in question) and a “control group” (a group that experiences no intervention). When this is done, it is generally presumed that any sufficiently large differences that emerge between the treatment and control groups were caused by the program.

Many, including us, consider the randomized controlled trial to be the “gold standard” in terms of causal attribution. However, there are often cases in which randomized controlled trials are politically, financially or practically non-feasible, and there are a variety of other techniques for attributing causality, including:

- Instrumental variables. An “instrumental variable” is a variable that affects the outcome of interest (for example, income) only through its impact on the intervention/program of interest (for example, access to schooling). An example of such an approach is Duflo 2001, which examines a large-scale government school construction program; it reasons that people who lived in districts that the program reached earlier got better access to education, through a “luck of the draw” that could be thought of as similar to randomization, so any other differences between people who lived in such districts and other people could fairly be attributed to differences in access to education, rather than other differences.We are open to the possibility of a compelling instrumental-variables study, but in practice, it seems that we see very few instrumental variables that are highly plausible as meeting the criteria, and many that seem very questionable. For example, a a paper by McCord, Conley and Sachs uses malaria ecology as an instrument for mortality, implying that the only way malaria ecology could affect the outcome of interest (fertility) is through its impact on mortality. However, Sachs has elsewhere argued that malaria ecology affects people in many ways other than through mortality, and we believe this to be the case.

- Regression discontinuity. Sometimes there is a relatively arbitrary “cutoff point” for participation in a program, and a study may therefore compare people who “barely qualify” with people who “barely fail to qualify,” along the lines of this study on giving children vouchers to purchase computers. We believe this method to be a relatively strong method of causal attribution, but (a) there tend to be major issues with external validity, since comparing “people who barely qualified with people who barely failed to qualify” may not give results that are representative of the whole population being served; (b) this methodology appears relatively rare when it comes to the topics we focus on.

- Using a regression to “control for” potential confounding variables. We often see studies that attempt to list possible “confounders” that could serve as alternative explanations for an observed effects, and “control” for each confounder using a regression. For example, a study might look at the relationship between education and later-life income, recognize that this relationship might be misleading because people with more education may have more income to begin with, and therefore examine the relationship between education and income while “controlling for” initial income.We believe that this approach is very rarely successful in creating a plausible case for causality. It is difficult to name all possible confounders and more difficult to measure them; in addition, the idea that such confounders are appropriately “controlled for” usually depends on subtle (and generally unjustified) assumptions about the “shape” of relationships between different variables. Details of our view are beyond the scope of this post, but we recommend Macro Aid Effectiveness Research: A Guide for the Perplexed (authored by David Roodman, whom we have written about before) as a good introduction to the common shortcomings of this sort of analysis.

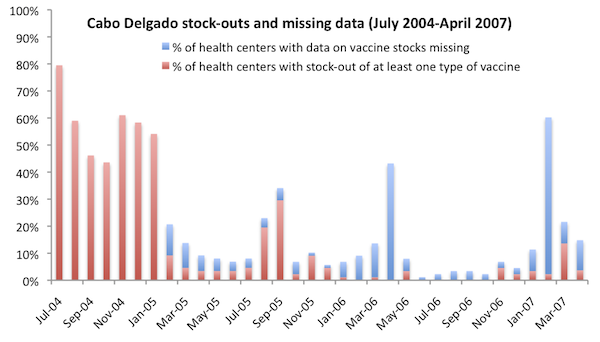

- Visual and informal reasoning. Researcher sometimes make informal arguments about the causal relationship between two variables, by e.g. using visual illustrations. An example of this: the case for VillageReach includes a chart showing that stock-outs of vaccines fell dramatically during the course of VillageReach’s program. Though no formal techniques were used to isolate the causal impact of VillageReach’s program, we felt at the time of our VillageReach evaluation that there was a relatively strong case in the combination of (a) the highly direct relationship between the “stock-outs” measure and the nature of VillageReach’s intervention (b) the extent and timing of the drop in stockouts, when juxtaposed with the timing of VillageReach’s program. (We have since tempered this conclusion.)We sometimes find this sort of reasoning compelling, and suspect that it may be an under-utilized method of making compelling causal inferences.

“Publication bias” is a broad term for factors that systematically bias final, published results in the direction that the researchers and publishers (consciously or unconsciously) wish them to point.

Interpreting and presenting data usually involves a substantial degree of judgment on the part of the researcher; consciously or unconsciously, a researcher may present data in the most favorable light for his/her point of view. In addition, studies whose final conclusions aren’t what the researcher (or the study funder) hoped for may be less likely to be made public.

Publication bias is a major concern of ours. As non-academics, we aren’t easily able to assess the magnitude and direction of this sort of bias, but we suspect that there are major risks anytime there is a combination of (a) a researcher who has an agenda/”preferred outcome”; (b) a lot of leeway for the researcher to make decisions that aren’t transparent to the reader. We’d guess that both (a) and (b) are very common.

When we evaluate a study, we consider the following factors, all of which bear on the question of how worried we should be that the paper reflects “the conclusions the researcher wanted to find” rather than “the conclusions that the data, impartially examined, points to”:

- What are the likely motivations and hopes of the authors? If a study is commissioned/funded by a charity, the researcher is probably looking for an interpretation that reflects well on the charity. If a study is published in an academic journal, the researcher is likely looking for an interpretation that could be considered “interesting” – which usually means finding “some effect” rather than “no effect” for a given intervention, though there are potential exceptions (for example, it seems to us that the relatively recent studies of microfinance would have been considered “interesting” whether they found strong effects or no effects, since the impacts of microfinance are widely debated).

- Is the paper written in a neutral tone? Do the authors note possible alternate interpretations of the data and possible objections to their conclusions? When we saw a white paper commissioned by the Grameen Foundation (at the time, the most comprehensive review of the literature on microfinance we could find) making statements like “Unfortunately, rather than ending the debate over the effectiveness of microfinance, Pitt and Khandker’s paper merely fueled the fire” and “The previous section leaves little doubt that microfinance can be an effective tool to reduce poverty” (a statement that didn’t seem true to us), we questioned the intentions of the author, and were more inclined to be pessimistic where details were scarce. In general, we expect a high-quality paper to proactively identify counterarguments and limitations to its findings.

- Is the study preregistered? Does it provide a link to the full details of its analysis, including raw data and code? As we have previously written, preregistration and data/code sharing are two important tools that can alleviate concerns around publication bias (by making it harder for questionable analysis decisions to go unnoticed).It seems to us that these practices are relatively rare in the field of economics, and less rare in the field of medicine.

- How many outcomes does the study examine, and which outcomes does it emphasize in its summary? We often see studies that look for an intervention’s effect on a wide range of outcomes, find significant effects only on a few, and emphasize these few without acknowledging (or quantitatively analyzing) the fact that focusing on the “biggest measured effect size” is likely to overstate the true effect size. Preregistration (see above) would alleviate this issue by allowing researchers to credibly claim that the outcome they emphasize was the one they had intended to emphasize all along (or, if it wasn’t, to acknowledge as much). However, even if a study isn’t preregistered, it can acknowledge the issue and attempt to adjust for it quantitatively; studies frequently do not do so.

- Is the study expensive? Were its data collected to answer a particular question? If a lot of money and attention is put into a study, it may be harder for the study to fall prey to one form of publication bias: the file drawer problem. Most of the field studies we come across involve collecting data on developing-world populations over a period of years, which is fairly expensive, for the purpose of answering a particular question; by contrast, studies that consist simply of analyzing already-publicly-available data, or of experiments that can be conducted in the course of a day (as with many psychology studies), seem to us to be more susceptible to the file-drawer problem.

- Effect size and p-values. A study will usually report the “effect size” – the size of the effect it is reporting for the program/treatment – in some form, along with a p-value that expresses, roughly speaking, how likely it is that an effect size at least as big as the reported effect size would have been observed, by chance, if the treatment fundamentally had no effect.We find the effect size useful for obvious reasons – it tells us how much difference the program is reported to have made, and we can then put this in context with what we’ve seen of similar programs to gauge plausibility. We find the p-value (and, related, reports of which effects are “statistically significant” – which, in the social sciences, generally means a p-value under 5%) useful for a couple of reasons:

- Even a very large observed effect (if observed in a relatively small sample) could simply be random variation. We generally emphasize effects with p-values under 5%, which is a rough and common proxy for “unlikely to be random variation.”

- The p-value tends to be considered important within academia: researchers generally emphasize the findings with p-values under a certain threshold (which varies by field). We would guess that most researchers, in designing their studies, seek to find a sample size high enough that they’ll get a sufficiently low p-value if they observe an effect as large as they hope/expect. Therefore, asking “is the p-value under the commonly accepted threshold?” can be considered a rough way of asking “Did the study find an effect as large as what the researcher hoped/expected to find?”

- Sample size and attrition. “Sample size” refers to the number of observations in the study, both in terms of how many individuals were involved and how many “clusters” (villages, schools, etc.) were involved. “Attrition” refers to how many of the people originally included in the study were successfully tracked for reporting final outcomes.In general, we put more weight on a study when it has greater sample size and less attrition. In theory, the reported “confidence interval” around an effect size should capture what’s important about the sample size (larger sample sizes will generally lead to narrower confidence intervals, i.e., more precise estimates of effect size). But (a) we aren’t always confident that confidence intervals are calculated appropriately, especially in nonrandomized studies; (b) large sample size can be taken as a sign that a study was relatively expensive and prominent, which bears on “publication bias” as discussed above; (c) more generally, we intuitively see a big difference between a statistically significant impact from a study that randomized treatment between 72 clusters including a total of ~1 million individuals (as an unpublished study on the impact of vitamin A did) and a statistically significant impact from a study that included only 111 children (as the Abecedarian Project did), or a study that compared two villages receiving a nutrition intervention to two villages that did not (as with a frequently cited study on the long-term impact of childhood nutrition).

- Effects of being studied? We think it’s possible that in some cases, the mere knowledge that one has been put into the “treatment group,” receiving a treatment that is supposed to improve one’s life, could be partly or fully responsible for an observed effect. One mechanism for this issue would be the well-known “placebo effect.” Another is the possibility that people might actively try to get themselves included in the treatment group, leading to a dynamic in which the most motivated or connected people become overrepresented in the treatment group.The ideal study is “double-blind”: neither the experimenters nor the subjects know which people are being treated and which aren’t. “Double-blind” studies aren’t always possible; when a study isn’t blinded, we note this, and ask how intuitively plausible it seems that the outcomes observed could have been due to the lack of blinding.

- External validity. Most of the points above emphasize “internal validity”: the validity of the study’s claim a certain effect occurred in the particular time and place that the study was carried out in. However, even if the study’s claims about what happened are fully valid, there is the additional question: “how will the effects seen in this study translate in other settings and larger-scale programs?”We’d guess that the programs taking place in studies are often unusually high-quality, in terms of personnel, execution, etc. (For example, see our discussion of studies on insecticide-treated nets: the formal studies of net distribution programs involved a level of promoting usage that large-scale campaigns do not and cannot include.) In addition, we often note something about a study that indicates that it took place under unusual conditions (for example, a prominent study of deworming took place while El Nino was bringing worm infections to unusually high levels).

We believe that RCTs have multiple qualities that make them – all else equal – more credible than other studies. In addition to their advantages for causal attribution, RCTs tend to be relatively expensive and to be clearly aimed at answering a particular question, which has advantages regarding publication bias. In today’s social sciences environment – in which preregistration is rare – we think that the property of being an RCT is probably the single most encouraging (easily observed) property a study can have, which has a practical implication: we often conduct surveys of research by focusing/starting on finding RCTs (while also trying to include the strongest and most prominent non-RCTs).

That said, the above discussion hopefully makes it clear that we ask a lot of questions about a study besides whether it is an RCT. There are nonrandomized studies we find compelling as well as randomized studies we don’t find compelling. And we think it’s possible that if preregistration were more common, we’d consider preregistration to be a more important and encouraging property of a study than randomization.