This is the final post (of five) we have made focused on our self-evaluation and future plans.

This post lays out highlights from our metrics report for 2012. For more detail, see our full metrics report (PDF).

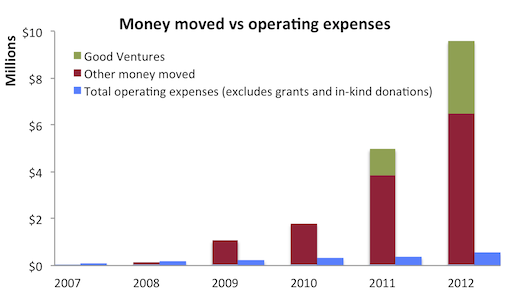

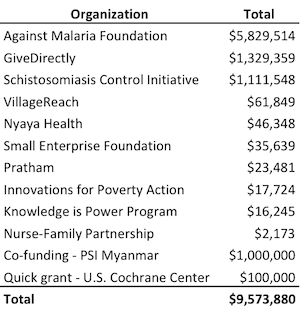

1. In 2012, GiveWell tracked $9.57 million in money moved based on our recommendations, a significant increase over past years.

2. Our #1 charity received about 60% of the money moved and our #2 and #3 charities each received over $1 million as a result of our recommendation. Organizations that we designated “standouts” until November (when we decided not to use this designation anymore) received fairly small amounts. $1.1 million went to “learning grants” (details here and here) that GiveWell recommended to Good Ventures.

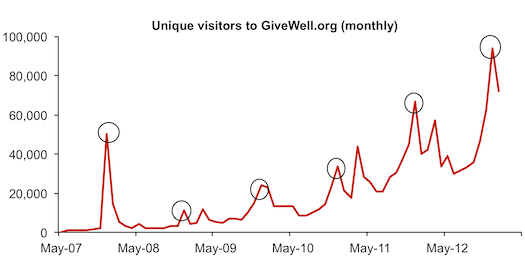

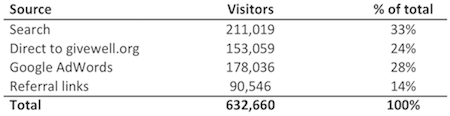

4. Web traffic continued to grow. A major driver of this growth was Google AdWords, which we received for free from Google as part of the Google Grants program. As in prior years, search traffic (both organic and AdWords) provided the majority of the traffic to the website. Traffic tends to peak in December of each year, circled in the chart below.

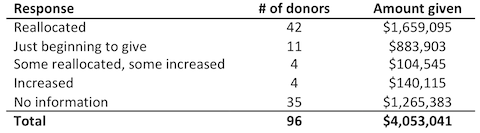

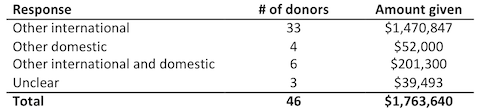

What effect has GiveWell had on your giving?